A HISTORY OF THE DISCIPLES ON THE WESTERN RESERVE

By Emanuel Daugherty

(an expansion and update of material originally presented at 1979 Memphis School of Preaching lectures)

Webster defines “heritage” as “property that descends to an heir, something transmitted by or acquired from a predecessor; legacy, tradition, birthright. Heritage may imply anything passed on to heirs or succeeding generations but applies usually to things other than actual property or money.” (Webster, 536).

The restoration of the New Testament Church is a worthy task. The restoration movement is our heritage in the churches of Christ. We have received that which was passed on to us from previous generations. The history of the Disciples on the Western Reserve is a vital part of that heritage. It is a thrilling and exciting history to read in its early stages. It is a heritage especially dear to me, since I was raised on the Western Reserve, living first in Warren, Ohio then in Braceville, Ohio, both in Trumbull County.

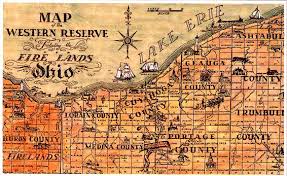

The Western Reserve is situated in the northeast part of Ohio. It is bounded on the north by Lake Erie, on the south by the 41st parallel, on the east by Pennsylvania, and on the west by Sandusky and Seneca counties. It extends north to south 50 miles and east to west for 120 miles. The area includes three million acres and is made up of the following counties: Ashtabula, Trumbull, Mahoning, Lake, Geauga, Portage, Cuyahoga, Summit, Medina, Lorain, Erie and Huron. The land was part of a larger part of western territory originally claimed by the colony of Connecticut, but then given to the newly formed United States. Out of this territory, three million acres were reserved as payment to soldiers who had served in the Revolutionary War and offered in the form of land grants. The first white settlers on the “reserve” were New England Revolutionary War veterans. These settlers brought their Yankee industriousness and quickly reshaped the wilderness into five mile square townships with schools, churches, and businesses at the heart of every village. They also brought their religion with them, primarily being Congregationalists and Baptists from the Pilgrim forefathers, but also including numbers of Methodists and Presbyterians. (Wilcox, 40).

In a twenty year period, approximately from 1827 to 1847, nearly 100 churches after the restoration order were established on the Western Reserve with an estimated 10,000 members. What were the factors which brought about this great surge of success in response to the Restoration plea?

Early Beginnings and Great Success

The different denominational groups on the Western Reserve shared several doctrinal and organizational viewpoints. Most held a Calvinistic view of salvation: salvation was the choice of the Sovereign God; a direct operation of the Holy Spirit was necessary since man was viewed as totally depraved; the operation of the Spirit would manifest itself in some sort of sign or “experience” so that the individual would know he was among the elect to be saved. But there was a dark side to Calvinism. Note Adamson Bentley’s description of his experience with the doctrine of election: “I used to take my little children on my knee, and look upon them as they played in harmless innocence about me, and wonder which of them was to be finally and forever lost! It can not be that God has been so good to me as to elect all my children! No, no! I am myself a miracle of mercy, and it can not be that God has been kinder to me than to all other parents. Some of these must be of the non-elect, and will be finally banished from God and all good. And now if I only knew which of my children were to dwell in everlasting burnings, oh! How kind and tender would I be to them, knowing that all the comfort they would ever experience would be here in this world!” (Hayden, 103).

Nearly all the groups, except the Baptists, practiced infant baptism. Nearly all the groups held to a creedal interpretation of the Bible, such as the Philadelphia Confession of Faith for the Presbyterians. And nearly every cabin had at least one book in it – the Bible. The availability of the Word of God as well as the ability to read it, formed a people receptive to the preaching of the Word.

The impact of the frontier on these religious people was also evident. There were no located ministers or pastors like what they had known east of the Appalachians or back in the Old World. Formal, trained preachers were rare. Most were farmers through the week, then itinerant circuit riders on the weekends.

Emotionalism was rampant on the frontier. It manifested itself in the form of crying, shaking, falling down, and other emotional exhibitions. Revival and camp meetings for three or four days’ time were popular gatherings attended by hundreds into the thousands. The religious fervor also united people in a way that rose above their denominational ties. Loosely organized “associations” permitted people of diverse religious viewpoints to come together for Bible readings, worship and doctrinal discussions. Denominational hierarchies had little to no control over scattered members who could enjoy the freedom of the frontier and move to the next valley if they had a doctrinal or practical disagreement with those in authority back East.

But the controversies that had created the various denominations followed to the frontier. Doctrinal differences were hotly debated. Questions relating to salvation and how to worship were intensely pursued for Biblical answers.

Into this climate of religious fervor on the frontier of the Western Reserve came the preachers advocating a plea for “a restoration of the ancient order of things.” (Campbell, CB, 126-28). First among these were preachers associated with Barton W. Stone in Kentucky. Hayden described their preaching: “They repudiated all creeds, contended for the Bible alone, were sticklers for the name ‘Christian,’ and being full zeal and gifted in exhortation, they gained many converts. They pursued the method known as the ‘mourning-bench system,’ . . . (Hayden, 80). Since these evangelists were holding evangelistic meetings in eastern Ohio, they were close to Campbell’s home in Bethany, Virginia across the Ohio River. One of these preachers, John Secrest came to Campbell to talk about the gospel. Secrest was soon persuaded that baptism was “for the remission of sins,” a position first advocated by Thomas Campbell, and then advocated by his son in his debate with the Presbyterian M’Calla. (Bever, 136-37). This new insight spurred Secrest to change his approach in preaching. His preaching partner, Nathan J. Mitchell, described this change: “Having been taught the way of the Lord more perfectly, he went immediately to work to ‘Teach others also,’ and labored zealously with the members of churches he had organized, to show them the importance of baptism. . . . Secrest preached boldly and fearlessly, faith in Christ, repentance unto life, and immersion by the authority of Christ into the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, in order to remission of sins. In the course of two years, or less, he immersed, upon profession of their faith in the Son of God, at least three thousand persons in eastern Ohio.” (Bever, 135).

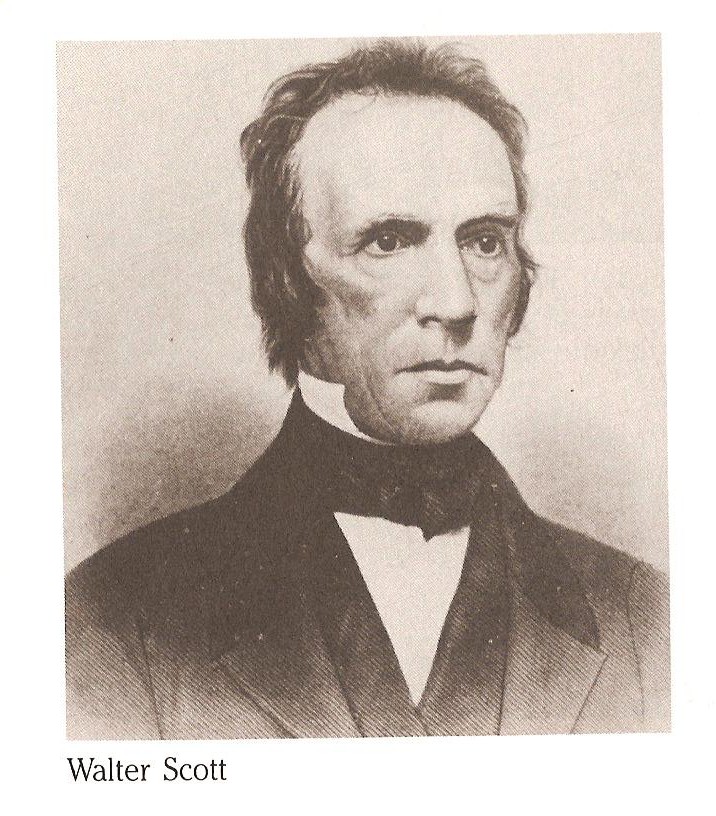

The remarkable success of the ‘Stoneite’ preachers spurred Campbell and others to rethink their views about evangelism. Before this time, Campbell had only started two congregations, Brush Run and Wellsburg in Virginia. Campbell had been more of a church organizer than an evangelist. Part of this may have stemmed from Campbell’s dismissiveness of emotionalism in religion. “Campbell feared that the revival atmosphere often fostered a situation where a person responded to Christ more from an emotional appeal than from being convinced intellectually of the message of the gospel.” (Bever, 145). Despite these fears the success of John Secrest and others in evangelism, prompted Campbell and Walter Scott to attend the Mahoning Baptist Association meeting in August 1827 in New Lisbon, Ohio. Walter Scott became the first traveling evangelist of the association.

Walter Scott’s name has been long associated with the success of the gospel on the Western Reserve. “The message of Scott seemed tailor-made for solving the religious problems of the frontier. His appeal was for the individual to initiate the conversion process. All one needed for salvation was the word God, rationally understood. The Bible was the ultimate authority for all religious questions, and the imposition of ‘foreign creeds,’ and non-biblical regulations was discouraged.” (Hicks, 214). Scott was credited as being the first to organize the gospel requirements for the conversion of sinners: “(1) Faith; (2) Repentance; (3) Baptism; (4) Remission of sins; (5) The Holy Spirit; (6) Eternal life, through a patient continuance in well doing.” (Hayden, 71). These were later condensed into five and brilliantly used in Scott’s “five finger exercise.”(Baxter, 184-85). But Scott had more than an organized way of seeing the response to the gospel. “Scott was tireless, often speaking in a grove in the afternoon and a private dwelling at night, which sometimes continued past midnight.” (West, 252). “And in those stirring times it was not unusual for those who, on such occasions, felt the power of truth, to be baptized before the morning dawned. The beautiful Mahoning became a second Jordan, and Scott another John calling on people to prepare the way of the Lord.” (Ibid.). Scott’s preaching was more in tune with Campbell’s rational approach as he led men away from emotionalism and “experimental religion.” “Walter Scott was convinced that the only true way to preach the gospel was the way the apostles did it – make Christ the center of the message and then build the sermon on His authority.” (West, 258). Scott’s belief in a rational presentation of the gospel “restored,” was brought home with conviction by the response of his first convert, William Amend. Scott had been preaching at New Lisbon, Ohio. A man who arrived late for the message sat down at the back of the room as Scott was finishing his sermon. When Scott had finished his conclusion, surprisingly, the man who arrived late came forward to obey the gospel. Later, Scott wrote a note to the man, asking him how he knew to respond to the sermon, when he had only heard the end of it. Amend’s reply is a classic example of what would be repeated on the Western Reserve: “I was baptized on the 18th of Nov., 1827, and will relate to you a circumstance which occurred a few days before that date. I had read the second chapter of Acts, when I expressed myself to my wife as follows: ‘Oh this is the gospel; this is the thing we wish, the remission of our sins! Oh, that I could hear the gospel in those same words as Peter preached it! I hope I shall some day hear, and the first man I meet who will preach the gospel thus, with him I will go.’ So, my brother, on the day you saw me come into the meeting house, my heart was open to receive the word of God, and when you cried, ‘The Scripture shall no longer be a sealed book, God means what He says. Is there any man present who will take God at His word and be baptized for the remission of sins,’- at that moment my feelings were such, that I could have cried out ‘Glory to God! I have found the man whom I have long sought for.’ So I entered the kingdom, when I readily laid hold of the hope set before me. William Amend.” (Hayden, 77-78). Over the next two years more than 3000 people would be baptized through the preaching of Scott, William Hayden, Aylett Raines, Adamson Bently, Marcus Bosworth, John Henry and many others. Meeting in homes, barns, schools, under trees or brush arbors, the people of the Western Reserve abandoned their creeds and covenants, confessions of faith and doctrines of men to accept salvation on the terms of the gospel alone.

Though Alexander Campbell was not an evangelist per se, his influence was felt throughout the region. Campbell’s Sermon on the Law, first preached at Cross Creek in Brooke County, Virginia had been a bombshell for the Redstone Baptist Association. In it Campbell declared, “Moses had the bud, the Jews had the blossom, and now Christians have the full fruit of grace.” Campbell pointed out that men were not under the law of Moses, but under Christ; not under the law, but the gospel; not under the Jewish dispensation, but under the Christian dispensation. Twenty-two preachers were present on the occasion and to them, Campbell was preaching heresy. They set out to expel him and the Brush Run congregation from the Redstone Association, but before that could happen, Campbell and Brush Run became a part of the Mahoning Baptist Association whose congregations were mostly found on the Western Reserve in Ohio. Through this association as well as his debates with Walker and M’calla in 1820 and 1824, respectively, Campbell promoted his understanding that the Bible taught baptism by immersion for the remission of sins. Articles appearing in the Christian Baptist in 1828 helped to advance Campbell’s views connecting baptism to the forgiveness of sins. (Bever, 147). As West summarized, . . .his [Campbell’s] influence on the movement’s evangelism was remarkable, as seen in the year 1827, the apex of the Restoration Movement’s evangelistic endeavors.” (West, 259).

Decline and Apostasy

But success in the gospel was not without its problems. Part of the problem was just the humanness of it all. Wherever there are individuals banded together, whether in families, schools, or churches, there will be disagreements from time to time. Some of these problems were overcome by the churches on the Western Reserve, but some were not. The newly planted churches did not always have a stable foundation. Individuals without knowledge of the nature of the Bible groped their way along as they slowly made their way out of their denominational practices. The focus on “first principles” or fundamentals in salvation, led to a lack of internal growth on the part of many individuals. Continuity in leadership was also a problem. The early leaders of the movement like Stone, the Campbells, and Walter Scott were dynamic personalities whose self-sacrifice, hard labor and Bible knowledge were not readily replaced after their deaths.

Migration to the West diminished the Lord’s Church on the Western Reserve. Westward expansion proved to be a mixed blessing. This population movement, at times weakened the churches that were left behind on the Western Reserve. But it also led to the planting of many more churches by those who carried the gospel message with them.

Mormonism made an impact on a few churches. Sidney Rigdon, an influential preacher was given to extravagant imaginations and this proved to be a fertile field for Mormon fantasies. A couple of Mormon emissaries arrived in Kirtland, Ohio in the fall of 1830. Rigdon, who had been rebuked by Alexander Campbell a few months earlier for trying to get the Disciples to accept a communal, common property living scheme, was humiliated and alienated. He readily received the Mormons and soon the entire church at Kirtland was swept away. Attempts by Campbell and others failed to bring Rigdon back to the Restoration ranks. That winter Joseph Smith arrived from New York with other followers. The Mormons claimed to work miracles and the incredulous followed their claims. Among these was Symonds Ryder, a leader in the church at Hiram, Ohio. After making several inroads in the Hiram congregation a revelation from Smith was given that Ryder was to be made an elder in the church, but Ryder began to doubt the truthfulness of the revelation when his name was misspelled. When another revelation surfaced that all who had property were to give it over into the hands of Smith for the good of the church, Ryder and another leader by name of Booth took counsel together and determined to undo what they had done in influencing people to join the Mormons. Smith, Rigdon and their Mormon followers were then given notice to leave or face the consequences. On the night of March 4, 1832, a mob of 60 men divided into two groups and tarred and feathered Smith and Rigdon. Shortly thereafter, the Mormons left Hiram and returned to Kirtland. After a year or two the Mormons migrated to Illinois and eventually Rigdon split with the Mormon leadership and went to Missouri while the main body of Mormons settled in Salt Lake City, Utah. (Clarke, 11-15).

Millennial mania also was a factor that created problems on the Western Reserve. By 1830, the great response to the preaching of Scott, Secrest and others convinced many Christians that this must be the beginning of the millennial reign of Christ. Hayden gives insight into the fervor of the times: “This hope of the millennial glory was based on many passages of the Holy Scriptures. All such scriptures as spoke of the ‘ransomed of the Lord returning to Zion, with songs and everlasting joy upon their heads: that they should obtain joy and gladness, and that sorrow and sighing should flee away,’(Isa. 35:10), were confidently expected to be literally and almost immediately fulfilled. These glowing expectations formed the staple of many sermons. They were the continued and exhaustless topic of conversations. . . . Millennial hymns were learned and sung with a joyful fervor and hope surpassing the conception of worldly and carnal professors.” (Hayden, 183-84). One of these hymns opened with these lines:

“The time is soon coming by the prophets foretold,1

When Zion in purity the world will behold,

For Jesus’ pure testimony will gain the day,

Denominations, selfishness will vanish away.”

The fervor was seen in Campbell’s closing of his early paper, the Christian Baptist, and the beginning of his new paper, The Millennial Harbinger. But the fervor became excess that slowed evangelism and church development. “Some of the leaders in these new discoveries, advancing less cautiously as the ardor of discovery increased, began to form theories of the millennium.” (Hayden, 185). Passages like Zechariah 14 were literally interpreted and offered as evidence for the literal reign of Jesus in physical Jerusalem. Foremost among these millennial mania leaders were Walter Scott and Sidney Rigdon. “Scott had a vein of enthusiasm, to which these millennial prospects were very congenial. He was led on in the brilliant expectations by the writings of Elias Smith, of New England, whose works had fallen into his hands. In a letter to Dr. Richardson, written in New Lisbon, April, 1830, he says the book of Elias Smith, on the prophecies, is the only sensible work on that subject he had seen.” (Hayden, 186). The writings of this Christian Connection preacher from New England seem to have been the origin of millennial theories among the Disciples on the Western Reserve. It should be remembered that a large number of those living on the Reserve had migrated from New England and probably formed “Connection” churches that were quickly absorbed into the Disciples fellowship. Also “Connection” preachers had been helpers to “Stone” preachers like John Secrest in 1827. “Rigdon, who always caught and proclaimed the last word that fell from the lips of Scott or Campbell, seized these views, and with the wildness of his extravagant nature, heralded them everywhere.” (Ibid.). Rigdon’s departure with the Mormons helped to cool some of the millennial ardor among the Disciples on the Western Reserve. Campbell also, being more prudent and realizing that millennial theories were diverting attention from the practical work of the gospel, sought to correct and balance this extreme through a series of articles appearing in the Millennial Harbinger in 1834 under the title “The Reformed Clergyman.” The effect of these articles helped to return the Disciples to a balanced view of the return of Christ and to focus on a return to preaching the gospel.

Missionary Society questions began for the Restoration movement at large in 1849, but the ground work for them had been laid on the Western Reserve long before then. The Baptist Associations were the predecessors to the societies. Note this description of these meetings: “The association was the Baptist answer to ecclesiastical cooperation. It was a council of a small number of congregations in a given geographical district. The purpose of the association was in the mutual improvement and inspiration of its members, the sharing of ideas, and protection against heretics and imposters. Associations usually met annually for two or three days, generally in the fall of the year.” (Shaw, 33). Campbell had joined the Mahoning Baptist Association in 1820 before he could be expelled from the Redstone Baptist Association for his anti-Calvinism. Scott had been sent out as evangelist for the Mahoning Association in 1827. But in 1830 a move was made to disband the Mahoning association since it was not found to be authorized by the New Testament. John Henry, a young evangelist made the motion. Hayden described the motion and its aftermath. “His meaning was apparent when he arose, soon after, and moved that the association, as an advisory council, be now dissolved. The resolution was offered, put and passed so quickly, that few paused to consider the propriety or effect of it. The most seemed pleased; but not all. The more thoughtful regretted it as a hasty proceeding. Mr. Campbell arose and said: “Brethren, what now are you going to do? Are you never going to meet again?’ This fell upon us like a clap of thunder, and caused a speedy change of feelings. Many had come forty or fifty miles, in big wagons even, so eager to enjoy this feast of love. Never to meet again! For a little time joy gave place to gloom. Campbell saw there was no use in stemming the tide and pleading for the continuance of the association, even in a modified form. The voice of the reformation, at this juncture, was for demolition, and Scott was thought to favor the motion. Mr. Campbell then proposed that the brethren meet annually hereafter for preaching the gospel, for mutual edification, and for hearing reports of the progress of the cause of Christ. This was unanimously approved. Thus ended the association, and this was the origin of the yearly-meeting system among us.” (Hayden, 296). One cannot read Hayden’s History of the Disciples on the Western Reserve and not get the impression that one of the purposes of his book was to serve as apology for the Missionary Society. Hayden called the disbanding an “evil.” He believed it an “apostasy” from the first principles that guided the Disciples. He said that the association’s evangelistic arm “ought to have been preserved, guarded, and perhaps, improved.” (Hayden, 297). In the final chapter of his history, “Lessons of Our Forty years’ Experience,” Hayden drives home his point. “Other religious bodies could have taught us wisdom, if we had not spurned everything that the fingers of ‘sectarianism’ had touched.” (Hayden, 457). “Our gospel has won many friends who have been lost to us through feebleness of plan and want of system.” (Hayden, 458). “The cry ran – clear away the rubbish, that the foundations of the Lord’s house may be laid. Reformation is one thing, demolition another, and restoration still another. Discrimination did not well rule the hour.” (Hayden, 459). “All our past history proclaims the necessity of a combination of effort to advance the gospel.” (Hayden, 461). After noting the successful establishment of the Eclectic Institute (Hiram College) by the northeastern Ohio churches, he then admonished: “This confidence is transferring itself to our missionary work. Around this society let it rally till it shall become a permanent power in the land!” (Hayden, 463). The disbanding of the Mahoning Association in 1830 prefigured the problem that the Missionary society would propose. Once an institution has been created, it will of necessity be involved in its own perpetuation. Society defenders appealed to it as an expedient to conduct evangelism. But before anything can be an expedient, it must first be shown to be authorized by the New Testament. God is to be glorified in the Church (Eph. 3:21). There is no authority for Missionary societies in the New Testament. The local church, under their eldership, selects and supports preachers or cooperates with other congregations.

Music questions also presented themselves to the churches situated on the Western Reserve. As they became firm defenders of the Missionary societies, it was not surprising that they also accepted the use of instrumental music in worship. The society involved the work of the church and the instrument was added to the worship of the church. Both involved a changed application of the motto “Speak where the Scriptures speak; be silent where the Scriptures are silent.” This silence was interpreted as permissive rather than prohibitive in nature and instrumental music began to be incorporated into the churches. In many places it began first in Sunday school activities for the young people. In addition to instrumental music, choirs and choruses also found their way into the worship of the Church. Shaw provides this summary of the impact of the music issue: “Though the older disciples in Ohio, many of them, went to their graves protesting against mechanical music, most of the churches gradually began accepting it.” (Shaw, 223). But the apostasy was not 100%. “A few isolated rural churches, however, that had never cooperated with the brethren anyway, became anti-organ churches.” (Shaw, 224).

Misguided zeal also was a factor in the decline and apostasy of the churches on the Western Reserve. The twenty year period of great evangelistic success from 1827-1847 must be seen as a case of “evangelism out-running leadership.” The lack of development in leadership after the New Testament order with elders, deacons, and evangelists to solidify the churches was a great contributor to the deterioration of many congregations. This failure to develop sound leadership allowed the doctrinal errors that came along in the next generation. The issues of the missionary societies, instrumental music in worship and increasing accommodation to modernist philosophies led to decline and apostasy on the Western Reserve. By 1900, most of the churches established in the early days became numbered with the Disciples of Christ or Independent Christian Churches.

Revival and Present Problems on the Western Reserve

The 1906 U. S. Census report officially acknowledged the division between churches of Christ and the Disicples and Christian churches. Churches pursuing the Restoration plea began to be re-established on the Western Reserve by itinerant evangelists coming from the “few, isolated rural churches” that had determined to adhere to Bible authority in their work and worship. A. A. Bunner, a native of Marion County West Virginia came to Cleveland, Ohio in 1919 to establish a church. The lure of regular pay for work also brought many Christians from rural communities to live in the towns and cities of the region. The industrial centers for steel, tires, and transportation were to be found on the Reserve and in the Upper Ohio Valley stretching from Cleveland, Ohio to Warren and Youngstown, across the upper panhandle of West Virginia to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. New congregations after the New Testament pattern began to emerge throughout the period between the World Wars and the Depression. Generally, these churches have been smaller and are fewer in number than in the glory days of Campbell and Scott. For example, the church in Warren began in the early 1940’s. The church at Windham was re-established in 1953. But even after the re-establishment of New Testament churches on the Western Reserve, there have been troubles which have disrupted the fellowship of the church.

Non-institutional views or anti-ism as it was known made a big impact on the churches in Akron, Ohio in the 1950’s. In the late 1960’s and early 70’s the AD 70 doctrine began in the church in Warren, Ohio under the preaching and writing of Max King. This doctrine refutes all that the New Testament has to say about the establishment of the Church, the Second Coming of Christ, the general resurrection of the dead, the end of the world, and final judgment. King believes these things all occurred in the fall of Jerusalem in AD 70. Efforts to meet this error have been many. Gus Nichols met Max King in debate in Warren, Ohio in 1973. Franklin Camp and Robert Taylor held written discussions with King. Faithful gospel preachers in the Ohio Valley led the way to refute this doctrine. Among these were Charles Aebi and Clifton Inman, Clarence Deloach, and Terry Varner. Varner put his studies about the doctrine in a book titled Studies in Biblical Eschatology, vol. 1. Though several churches on the Western Reserve were affected by this doctrine, its influence has greatly waned. King and his family have now left the area and are involved in the Community Church movement in Colorado. Unfortunately, King’s doctrine continues to be felt in various places where his books have been received by those more interested in speculation rather than the simplicity of the New Testament.

Conclusion

The Restoration of New Testament Christianity must continue. Its plea is just as powerful and valid as when first spoken. The problems encountered by the Restoration in no way invalidate its plea. Problems will always come when men insist on their own way over the Bible way. There is a rich heritage in the Restoration on the Western Reserve. It contains a mixed legacy that is both encouraging and discouraging. But we can still learn from its triumph and tragedies. “Ask the blessed dead, they will tell you . . . they preached the gospel. They were no mere essayists. They were not theorizers, nor speculatists. They preached Christ and Him crucified. In this they were a unit. The same gospel was preached in every town, county and school district. They used their Bibles. They read, quoted, illustrated and enforced the Holy Scriptures. This lesson is important. We must ‘preach the word,’ not something about the gospel, but the gospel itself. Some of our preachers should sit at the feet of the departed veterans, and learn to speak and enforce Bible themes in Bible words. Let us have more Scripture, in its exact meaning and import; more gospel, more of Jesus, His will, His mission, and His work. This was their power. It will be ours. Most of all and last of all, we impress this lesson: preach the gospel in season, out of season. Preach it as Peter preached, as Paul preached it. Be not weak, nor ashamed of its facts, commands and promises, as delivered to us by our fathers; and to them by the holy apostles.” (Hayden, 464).

Works Cited

Baxter, William. Life of Elder Walter Scott. Nashville: Gospel Advocate, reprint of original.

Bever, Ronald. “The Influence of the 1827-1829 Revivals on the Restoration Movement,” Restoration Quarterly vol.10 no.3 (1967):134-147.

Campbell, Alexander. “A Restoration of the Ancient Order of Things, no. 1” Christian Baptist vol. 2 no. 7 (Feb. 7, 1825):126-128. This initial article would be followed by 31 others of the same title.

Clarke, Vesta Ryder. History of the “Old South Road” aka Ryder Road aka Pioneer Trail. Hiram, OH: privately published, 1999.

Hayden, A. S. Early History of the Disciples on the Western Reserve. Indianapolis: Religious Book Service, reprint of 1875 original.

L. Edward Hicks. “Rational Religion in the Ohio Western Reserve (1827-1830): Walter Scott and the Restoration Appeal of Baptism for the Remission of Sin,” Restoration Quarterly vol.34 no. 4 (1992):207-219.

Shaw, Henry K. Buckeye Disciples. St. Louis: Christian Board of Publication, 1952.

Varner, W. Terry. Studies in Biblical Eschatology, vol. 1. Marietta, OH: Therefore Stand Publications, 1981.

Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary. Springfield, MA: G & C Merriam, 1976.

West, Earl I. “1827 Anus Mirabilis and Alexander Campbell,” Restoration Quarterly vol.16 no.3-4 (1973):250-259.

Wilcox, Alanson. A History of the Disciples in Ohio. Cincinnati: Standard Publishing, 1918