RACE RELATIONS IN THE RESTORATION MOVEMENT

by Bruce Daugherty

(originally presented at Florida School of Preaching lectures, Jan. 2015)

The development of Christian character is sorely needed today. No better guide for that development can be found than the Sermon on the Mount. The portrayal of life in the Kingdom by the Son of God challenges everyone who wears the name of Christ. The Florida School of Preaching and its director, Brian Kenyon are to be commended in selecting this study for the annual lectureship.

The pages of Restoration History give testimony as to how the principles of kingdom living were applied by those seeking to return to New Testament Christianity. As with many issues, race relations in the Restoration Movement are a mixture of triumph and tragedy. Like the Christians of first century Corinth , this historical testimony contains that which is praise worthy and that which is not (1 Cor. 11:2, 17, 22). May this examination of the pages of Restoration History assist Christians today to “hold fast to what is good” while “abstaining from every form of evil” (1 Thess. 5:21-22).

This study will confine itself to the relationship between whites and blacks, though the relationship between whites and Hispanics, Native Americans and other groups could all be considered under the broad term, “race relations.” Proceeding from this restricted view, race relations in the history of the United States follows a broad outline moving from slavery to emancipation to segregation to the Civil Rights movement to the present day. This study of race relations in the Restoration Movement will follow that same trajectory.

The restoration movement is that 19th century effort aimed at a return to the doctrine and practice of New Testament Christianity. It was a plea to set aside denominational creeds, councils, and confessions of faith to follow the authority of the New Testament. It was a plea for the unity of Christians on the basis of the will of Jesus as revealed in Scripture. This plea found fertile soil in the minds of men and women living on the American frontier in the early days of the 19th century. The response to the restoration plea was in the words of one of its earliest proclaimers “like fire in dry stubble.”(Stone, CM vol. 7 no. 8:244). By 1865, thousands of converts organized into hundreds of autonomous congregations formed a “noble brotherhood” that dotted the landscape from New England to the coasts of the Pacific and from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. (Lard, 251). Many of these churches were clustered in the Ohio Valley. This is not surprising since two of the earliest and most prominent leaders of the movement, Barton W. Stone and Alexander Campbell, made their homes in Kentucky and western Virginia respectively.

Ante-bellum Views

But this area in the cradle of the restoration movement was also home to “the peculiar institution” – slavery. While it is difficult to know how many of the Restorer’s owned slaves, it is clear that many were “deeply involved in the slavery dilemma.” (Harrell, vol. 1:93). In some ways, this was surprising since both Stone and Campbell opposed slavery and set the example of emancipating the slaves they had inherited.

The Cane Ridge revival of 1801 had been a turning point in the life of Barton Stone. As Stone experienced a new religious freedom, he determined to give physical freedom to the slaves he owned. His example also led others to free their slaves. He later wrote of his continued opposition to slavery.

All who know me, well know that for more than thirty years I have advocated the cause of liberty, and opposed unmerited, hereditary slavery. My honesty has been tested; for all in my possession I emancipated; nor did I send them out empty. (Stone, CM vol. 3 no. 8: 198).

The basis for Stone’s action was that slavery did not harmonize with the principles of the kingdom.

We view the period not far distant when African slavery shall no more be known in our happy country, when “mercy and truth shall meet together, and righteousness and peace shall kiss each other.” (Stone, vol. 7 no. 2: 63).

Stone urged his readers to make the necessary sacrifices to follow Christ – “they will forsake father and mother, brothers and sisters, husbands and wives, houses and lands, and slaves too when convinced of the evil, for the kingdom of heaven’s sake.” (Stone, vol. 7 no. 2: 64).

But Stone could not envision whites and blacks living together in a mutually free society. He became, like many Americans, including future President Abraham Lincoln, an advocate of colonization to return blacks to Africa.

“To free them among us, and let them live among us, is impolitic, as stubborn facts have proved. Were those now in slavery among us to be thus emancipated, I would instantly move to a distant land beyond their reach.” (Stone, vol. 3 no. 8: 199).

But not everyone followed Stone’s example of emancipation. Like other churches, slaves were a part of the Cane Ridge congregation, sitting in the balcony of the meeting house, separated from their masters below. Stone’s pious soul was vexed by the many friends and even relations who continued to own slaves, despite his passionate condemnation of the institution. As the years passed and colonization became less and less likely, Stone could not live between the two views any longer and moved to Jacksonville, Illinois in 1834.

Thomas Campbell also found slavery made his life difficult in Kentucky. He had moved to Burlington, Kentucky in 1819 to teach in a school and to preach in a local church. One Sunday in the summer of 1819 he invited some of the nearby slaves to come to the schoolroom where he read the Bible to them, and led them in singing hymns. The experience was enjoyable to teacher and students alike, and another service was arranged for a future date. The next day, Campbell was met by a local citizen who informed him that he had broken the law forbidding instruction to slaves except in the presence of two or more white witnesses. The “friend” assured the elder Campbell that no charges would be brought against him unless he repeated his Sunday meeting with the slaves. Campbell was shocked that a state would prohibit religious teaching to anyone, even to slaves. He protested, “Can the Word of God be thus fettered in a Christian land?” At great personal cost, Thomas Campbell left Kentucky to go where he could preach freely to all men. (McAlister, 182).

When Alexander Campbell married Margaret Brown in 1811, he inherited slaves along with his farm. Campbell emancipated his slaves, after giving them an education with his own children and teaching them a trade so that they could provide for themselves. (Richardson, vol. 1:502).

In his only involvement in politics, Campbell became a delegate to the 1829 Virginia Constitutional Convention. Part of his reasons for participating in the convention was to seek for abolition of slavery in Virginia. Campbell’s initiative was defeated but he did not stop his efforts opposing slavery. (Hale, 67).

Campbell utilized the pages of his paper, The Millennial Harbinger, to speak out on slavery. In the first issue, Campbell’s prospectus included:

Disquisitions upon the treatment of African slaves, as preparation to their emancipation and exaltation from their present degraded condition. (Campbell, MH vol. 1: 1).

Campbell held true to his word, and in 1830 he wrote his first article. Since Campbell was writing to whites, he appealed to “enlightened white self-interest.” (Hale, 69). Campbell explained that slavery in and of itself, was not wrong, since the Bible spoke of the relation of master and servant. But Campbell did believe that slavery in the United States was a system that created “mutual bondage” of black slaves serving white masters and of white masters becoming slaves to the system of slavery. He quoted Paul’s statement that “whatsoever you deliver yourselves up as servants, you are the slaves of that which you obey.”(Rom. 6:16). He pointed out that whites lived in slavery of fear of insurrections and uprisings. This fear was so strong that they prohibited education of slaves, which was the way of all tyrants “from the most intolerant and persecuting governments of the Pagan and Papal world.” Campbell said that such a view was the very opposite of “the genius of our government and constitution.” (Campbell, MH vol. 1: 132).

Alexander Campbell

Like Stone, Campbell could not envision an integrated society in America. (Haymes, 619). He too, was in favor of colonization or returning the slave to Africa. He called slavery

That largest and blackest blot upon our national escutcheon, that many-headed monster, that Pandora’s box, that bitter root, that blighting and blasting curse under which so fair and so large a portion of our beloved country groans . . . (Campbell, MH vol. 3: 86).

To remedy this situation that would bring liberty to blacks and compensate whites for their loss of property, Campbell proposed that some politician like Henry Clay to demonstrate that

An appropriation of ten millions per annum, for 15 or 20 years, would rid this land of the curse, and bind the union more firmly than all the rail roads, canals, and highways which the treasury of the union could make in half a century. (Campbell, MH vol. 3: 88).

Thus, with the slaves freed, and the white slave holders compensated, the slaves would be free to join the colony of former slaves in Liberia, West Africa. But Campbell also noted prophetically what would happen to the country if emancipation did not occur.

And as sure as the Ohio winds its way to the Gulph of Mexico, will slavery desolate and blast our political existence, unless effectual measures be adopted to bring it to a close while it is in the power of the nation – while it is called today. (Campbell, MH, vol. 3:88).

Campbell concluded his article by citing “Righteousness exalts a nation, but injustice is a reproach to any people.” (Prov. 14:34).

While Stone and the Campbells were moderate men, doing what they could to abolish slavery while living in slave states, there were also extremists on both sides of the question. These early leaders of the Restoration movement were trying to prevent the slavery issue from dividing the fellowship that they had worked so hard to create. But not all who followed them were as committed to unity as the early leaders. These men were known as “fire-eaters” and they did not care if the churches of the Restoration movement were consumed in their wake.

James Shannon was the outspoken defender of slavery in the Restoration Movement. Shannon, an immigrant from Ireland, had been trained for ministry in Belfast. After his arrival in the United States he converted to the cause of New Testament Christianity. Shannon became a widely respected educator as well as a preacher and served as President of Bacon College in Kentucky and the University of Missouri.

In 1849 and in 1855 Shannon made two public speeches defending slavery in Kentucky and Missouri respectively. Both speeches were published in tract form and widely circulated in slave territory. In these speeches, Shannon defended slavery as being approved by God since the master/slave relationship was found in Scripture (Eph. 6:5-9; Col. 3:22-4:1; Phile.). But Shannon never asked “whether the Bible encouraged the taking of taking of slaves or simply gave necessary guidance to an economic system already in place.” (Poyner, 115). It was obvious that Shannon’s speeches were aimed at Southern sympathizers, being filled with emotional appeals to rouse passions. He denounced the “foul demon of anti-slavery fanaticism” and “I hurl proud defiance in the viper teeth of abolitionism and the motley crew of his abettors and sympathizers.” (West, Trials, 302.).

Shannon had his critics in both North and South. D. S. Burnet, a preacher in Cincinnati described Shannon’s speech in Kentucky as “prostituting the Bible to an unholy cause.” (Poyner, 85). A New Orleans newspaper called Shannon’s speech in Missouri, “fanaticism run wild.” (West, Trials, 294). Shannon’s speeches breathed the air of radical southern politicians, and his fellow preacher, T. M. Allen stated that Shannon was “chin deep” in politics. (West, Trials, 304).

Radical abolitionists were also to be found in the Restoration Movement. As the years passed, it became obvious that efforts of emancipation and colonization were not to be realized. Southern people were too dependent on slaves for their economy. With this realization, abolition of slavery, by force if necessary, became the cause of many Northern disciples.

The Disciples abolitionists were a tenacious breed of Christian preachers – they were prophets obsessed with a sense of mission. The injunction to “do unto all men as you would they should do unto you” became to them the all-consuming design of Christianity. (Harrell, vol. 1:114).

This created a growing division between radical leaders like Ovid Butler and Pardee Butler and moderates like Alexander Campbell.

Two geographical centers of radical abolitionism emerged among the Northern restorers. One was the on the Western Reserve in Northeast Ohio and the other in central Indiana. John Boggs, Jonas Hartzell, and William Hayden were the most vocal leaders in Ohio. Despite the fact that the Western Reserve had once been the scene of Campbell’s greatest success, the Buckeye Disciples rejected Campbell’s moderation.

From 1845 on, there was a gradual alienation of affection between Ohio Disciples and the Bethany reformer. This was most noticed in lack of support to Bethany College, and the subsequent founding of Hiram College in 1849. (Shaw, 142).

In addition to promoting the abolitionist cause, some Ohio congregations were also part of the underground railroad for runaway slaves. (Shaw, 144).

Ovid Butler was a prominent lawyer and abolitionist in Indianapolis. For him, slavery was not merely an existing evil, but a sin. He attacked all Disciples who were not all out for abolition, which included Campbell. He too, could no longer support Bethany College and founded North-Western Christian University (now Butler University) in Indianapolis in 1850. Later he funded a paper, North-Western Christian Magazine with the fiery John Boggs as editor.

No place was more embroiled in the slavery issue before the Civil War than Kansas. “Bleeding Kansas” was the scene of violence by “border ruffians” coming from adjoining Missouri seeking to make the territory a slave state by popular vote as per the Kansas-Nebraska act. It was also the scene of abolitionist reprisals like that of John Brown’s violent massacre at Pottawatomie Creek. And Kansas was home to one of the most outspoken abolitionists found in the Restoration Movement, Pardee Butler. Butler was determined to keep slave holders out of the new territory. From the pulpit and with his pen, Butler continually attacked the slave element in the territory. His outspokenness soon caused him to be a marked man. In the town of Atchison, Kansas Butler was attacked by a mob and tarred and feathered. Later he was set adrift on a small log raft in the middle of the Missouri river. But Butler had “sand in his craw” and would continue to agitate against slavery. (Harrell, vol. 1: 115-116).

Campbell looked on the agitation of the abolitionist’s and decided to have none of it. To him, the abolitionists could only talk of the issue in terms of violence.

It shall only be discussed by the light of burning palaces, cities and temples, amidst the roar of cannon, the clangor of trumpets, the shrieks of dying myriads . . . the horrid din and crash of a broken confederacy . . . and the agonizing throes of the last and best republics on earth. (Lunger, 202).

To Campbell, the abolitionists had a blind spot in their love for humanity. According to Campbell, the abolitionists were “philanthropists who have forgotten that philanthropy includes the love of both master and servant, and contemplates justice and kindness to all.” (Lunger, 202). Samuel Church pointed out another blind spot in the vision of the abolitionists.

Slavery, be it good or bad, is not the voluntary choice of the present generation of the South. They inherit it, and all their established habits of thinking and acting, individually and socially – morally, politically, and religiously – are more or less, identified with it. If it’s existence be sinful, they are not conscious of it, and are unlikely to be enlightened by calling them thieves and villains. (West, Search, 331).

Campbell, while attacking abolitionists, ended by defending the slave owner. Commenting on Colossians 4:1, Campbell stated that if the Apostles had been like the abolitionists then the verse would read: “Masters, immediately emancipate your slaves, and pay them wages, or let them go and seek employment elsewhere.” (Lunger, 203). Since the Bible did not read that way, Campbell believed that abolitionists should cease calling slavery a sin and should stop making the issue a test of fellowship and dividing churches over it.

It is clear that Campbell was trying to navigate a middle course on the issue of slavery. But in so doing, Campbell had his own blind spot.

The most striking fact about his treatment of the slavery issue is that he almost never dealt with the subject from the point of view of its effects upon the slaves. Rather he was always concerned primarily with the effects of the system upon the slaveholder and his family, or upon the well-being of society in general, the unity of the church or order in the state. (Lunger, 231).

Henry Shaw concurred with that assessment:

Campbell found himself possessed by an understanding appreciation for the problems of his brethren, both North and South. He therefore took a mediating position. As a result, northern Disciples considered him pro-slavery and southern Disciples thought him anti-slavery. (Shaw, 140).

But by the time of the Civil War, no more middle ground was to be found, for the nation and for the churches of the Restoration.

Reconstruction and Segregation

The racial make-up of the churches of the Restoration Movement in the South was radically altered by the Civil War. Tolbert Fanning, editor of the Gospel Advocate, writing in 1872 described the difference:

Time was when thousands of the best informed colored people of the south, lived in full fellowship as members of the church of Christ, with their white brethren . . . Possibly, in no section of the earth, could so intelligent and cultivated colored Christians be found, as in the state of Tennessee. . . . Our colored brethren, some of whom at least we had aided in purchasing and setting at liberty . . . were completely alienated from us, and turned against us. The revolution was too sudden and too great, for the moral health of the freed people. They were induced to think, that all with whom they had formerly associated were oppressive, and enemies of the colored race. (Harrell, vol. 2, 160).

Two factors were at work in creating this situation. First was a desire on the part of blacks to be independent and in control of their own destinies, including religious institutions. Second was the attitude of whites toward the freedmen which manifested itself in paternalism, racial prejudice, and apathy.

The enthusiasm that the abolitionists had given to emancipation and the war was not matched by the same enthusiasm of taking the gospel to the 4 million free people. Early efforts at evangelism during the Reconstruction period were reflections of the period itself : initial enthusiasm, little practical knowledge of the realities of the situation, and finally disinterest.

In 1867, Orrin Gates, a ministerial student at Hiram College was stirred to action by a visit from G. W. Neely, a white evangelist from Alabama. $1300 dollars was pledged by fellow students at Hiram for the support of evangelistic work to be done by Gates among the freedmen in Lowndes County, Alabama. Gates, accompanied by a female schoolteacher, Mary Atwater, and in conjunction with Neely, began his work. But in less than six months, Gates had returned to Ohio due to threats of physical harm. Neely remained, though he was “ostracized from white society and threatened with death” for preaching to blacks. (Harrell, vol. 2: 166-67).

Other works supported by Northern Christians, centered on evangelism among blacks by supporting black preachers. Peter Lowery, a freeman living near Murfreesboro, Tennessee conducted a successful ministry which baptized many. Prior to the Civil War, Lowery had organized a Sunday school that numbered over 200 members and was supported by whites in Nashville, Tennessee. Lowery ran a successful livery that was worth $40,000. Lowery was able to purchase his freedom and the freedom of his mother, three brothers, and two sisters. The war left him penniless. Realizing the needs of the people, he sought to establish a school for instruction in basic education and teaching of farm and mechanical skills. Lowery began to raise funds for the purchase of a farm and the building of a mill which would employ students. Many whites supported and commended Lowery’s work. But the venture came to a halt when Lowery’s son, Samuel was found to be embezzling funds and sending out false work reports. (West, vol. 3, 177). The Lowery scandal demonstrated the difficulties involved in white support of black evangelists. Lack of good communication and limited knowledge of the workers created a climate of distrust and suspicion.

Paternalism was another contributing factor to the creation of separate black and white churches. Echoing the sentiments of Rudyard Kipling’s poem, The White Man’s Burden, some whites, proceeding from a view of racial superiority, were willing to support evangelistic work to African-Americans by African-Americans as long as blacks “kept their place” by being submissive and staying socially segregated. (Robinson, Two Old Heroes, 8-9). B. F. Manire, writing in 1898, voiced the paternalistic view of many white brethren:

Our common heavenly Father, in his overruling providence, brought them here, enslaved them here, emancipated them here, made them American citizens here, and placed us as guardians over them here, that through our instruction, examples, and assistance, they may be fitted for the great work God has planned for them to do . . . (Harrell, vol. 2, 162, italics mine bd).

Many African-Americans preferred to manage their own affairs, even if it meant less support, rather than having to kowtow to such paternalistic attitudes.

Racial prejudice also helped to erect walls of separation in the Restoration Movement. When John Cotton began a Sunday school for Negroes in 1868, he was shocked at the hostility of his fellow brethren in Missouri:

As soon as my own brethren and sisters, learned that I had consented to take charge of the black school, they immediately withdrew their children, turned the cold shoulder to me, and refused to allow their children to go to Sunday school to any man who would teach niggers. (Harrell, vol. 2, 172).

William K. Pendleton, writing in 1869, spoke of white hostility towards blacks found in the churches. “It is getting to be in the southern States, as it has long been in the northern, that the negro and the white man do not worship together. They do not go to the same place of worship so cordially, nor unite in the same fellowship so freely, as they formerly did.” (Harrell, vol. 2, 200). J. M. McCaleb acknowledged that white prejudices were at the heart of the difficulties in education and evangelism of African-Americans. “Race prejudice, however, stands as a great barrier to such work. If the white man makes it a custom to preach to them and mingle with them, he is severely criticized by his own people . . .” (Robinson, Two Old Heroes, 8). G. F. Gibbs, an evangelist in the Carolinas, spoke of the need for black evangelists to reach a black audience, “. . . I would remind that prejudice runs high and even among the negroes there is opposition to the whites teaching them . . .” (Gibbs, 3).

Early Voices Opposing Segregation

Segregation of the races was the social pattern of the larger culture within the United States from the Reconstruction period up to the Civil Rights movement. Following the “Plessy vs. Ferguson” decision of the Supreme Court, “separate but equal” became the official legal position of the United States. This was reinforced by the passage of “Jim Crow” laws in many communities. Within the churches of the Restoration Movement conformity to culture had created a “spiritually equal, but socially separate” approach to race relations. Many brethren found it easier to conform to the ways of the world rather than to challenge the written and unwritten social codes of the period. But there were a few voices that were willing to challenge racial segregation in the Church. (Daugherty, 39).

Believing slavery to be “an evil to the country and to the people,” David’s Lipscomb’s father sold his farm in middle Tennessee and moved to Illinois in 1834 to free the few slaves he owned. (Hooper, Call, 56). But Granville Lipscomb paid a price for faithfulness to conscience. While in Illinois, his wife and three children died from malaria. Unable to bear his grief, Granville Lipscomb returned to middle Tennessee with his sons David, William, and a little daughter, Keren. (West, Life and Times, 31). Years later, David Lipscomb, a son of the South, spoke of his own experiences in race relations.

I was raised among negroes. My mother died so early I do not remember her. I was cared for, for some years, greatly by a negro woman. Negro children were my playmates. I have always had the kindliest feelings for them. Yet I have always felt the race instincts strong. (Lipscomb, A Correspondence, 425).

David Lipscomb

These early experiences plus the fact that he had always worshiped in congregations that included blacks, first as slaves, then as freemen, gave Lipscomb a different view on race relations.

In 1907, Lipscomb was drawn into a controversy taking place in the Bellwood congregation regarding the inclusion of a young black woman in the worship services of the white congregation. The agitation reached the pages of the Gospel Advocate in a letter and its reply from S. E. Harris to E. A. Elam, front page editor of the Advocate. Harris believed that the presence of the “colored girl” would divide the church. His solution was for her to attend a black congregation meeting nearby, where she could worship with her own race. Elam, who was responsible for the young woman, replied that the agitation over the situation was motivated by “prejudice, selfishness, and a very great injustice” (Lipscomb, A Correspondence, 425). As the correspondence continued and the controversy in the Bellwood congregation refused to die, Elam asked David Lipscomb to intercede.

Lipscomb began by pointing to equality between individuals of every nation, tribe, country and social position as indicated in Galatians 3:28. Since this was true, no Christian had a right to treat the “least and despised” differently on the basis of family, race, social or political station. To do so was to object to Christ Himself (Matt. 25:40). Lipscomb went on to say:

I have never been satisfied of the righteousness of forming congregations in a community along race lines. In the days of Jesus and the apostles the race antagonism between Jew and Gentile was strong and bitter. Converts were made from both races. I find no evidence that they met in different places as separate congregations. Troubles arose over the race question, but these troubles were harmonized within the churches, and the wall of separation and division was weakened, not strengthened. (Lipscomb, A Correspondence, 425).

Lipscomb pointed his readers to the example of Christ. He said that there was something wrong in Christians gathering to remember the death and sufferings of Christ to lift up humanity and at the same time discouraging the lowly from the assembly. As he concluded the correspondence, Lipscomb made clear the narrow choice in the matter.

The only point really involved in this difficulty is, whether we will be led by the Spirit of Christ and the teachings of the Bible or by our prejudices against the negro. The besetting sin of humanity from the beginning has been to follow its own feelings instead of the word of God. To follow our prejudices and feelings instead of the will of God is to rebel against and reject God as our ruler. (Lipscomb, Negro in Worship, 521).

Lipscomb was a man of his times. Though he acknowledged the equality of the races he also accommodated the social customs of his day and argued for separate seating places for blacks and whites in congregations and even separate doors for entering and exiting the building. (Harrell, vol. 2, 199). Even the school founded by Lipscomb did not admit blacks until after the Civil Rights movement.

Another man who fought vigorously against racial discrimination was S. R. Cassius. Samuel Robertson Cassius was a forgotten trailblazer in the Restoration Movement. (Robinson, Forgotten, 11). Cassius was a former slave who became an untiring evangelist, educator, and outspoken critic of racial discrimination. Cassius was a “globe-trotting” evangelist, preaching primarily to African-Americans and establishing black congregations. In his lifetime Cassius preached throughout the United States and established more than 50 congregations. (Robinson, Forgotten, 17). The greatest scene of Cassius’ evangelism was Oklahoma where he labored for nearly 30 years. In 1899, Cassius established an Industrial School at Tohee, Oklahoma, modeled after Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute. Cassius spoke of his vision for the school.

Teach my people that the nation is looking forward to their boys and girls to make up the great industrial army of tomorrow; teach them that an education consists of more than learning to read and to write, and that industry means more than cooking and washing for the women, and barbering, preaching, waiting in hotels, and loafing for our men; teach them that the word “education” means to develop both mind and matter – it means the strengthening of both the physical and intellectual part of man. Once this is done, you produce a happy, independent people, who will be a credit to the nation and a safeguard to the republic. (Cassius, Tohee Industrial School, 14).

Cassius frequently reported on his work in the Christian Leader, an important journal for churches of Christ based in the northern section of the country. Cassius’ reason for reporting in the paper based in Cincinnati was his view that the Leader was “the only paper that gives to the Negro an unrestricted welcome.” (Cassius, April 5, 1904, 5). In the pages of the Leader, Cassius would tirelessly poke and prod his white brethren out of their indifference toward sharing the gospel with his race.

In 1920 Cassius wrote The Third Birth of a Nation. He believed it to be the first book written by a “colored man” to be published by churches of Christ. (Cassius, October 12, 1920, 9). The book was written for several purposes and can be interpreted in many contexts. (Robinson, To Save, 136-138). But the book also contained Cassius’s solution to the “race problem.” “I contend that there would be no race problem to solve if the so-called Christian people of America would take the word of God as the man of their counsel and its teachings as their rule of faith and practice.” (Cassius, Birth, 83). Cassius urged Christians to act in faith rather than fear regarding the social implications his solution would bring.

Our children would go to the same schools, learn the same lessons, and would daily receive instruction out of the same Bible and learn to love and honor the same God. One Christian would not despise another Christian because of race, color or any other condition, except it be that of ungodliness . . . Christians would not be afraid of social equality injuring their home, because the grace of God would cast out all fear. (Cassius, Birth, 83).

Cassius addressed “Jim Crowism” and spoke of its origins. “The world did not start the ‘Jim Crow’ law; it was started by the church because the white members of the church did not think that negroes were good enough to worship God in the same house that they did.” (Cassius, Birth, 84). For Cassius, proof of the Restoration plea would be seen in whether the gospel would be preached to all men regardless of race. Cassius explained,

Christianity means the things taught by Christ and his apostles, and being a Christian means doing the things taught by Christ and his apostles. The other churches, by their methods of religion, have failed to make the world of the Lord, the Man, this nation’s counsel. Therefore it is up to the Church of Christ to make good its boast that they are serving God just as God has ordered his servants in his word. (Cassius, Birth, 86. Italics in original).

Cassius believed that Christians were inconsistent when they sent support for mission abroad, but neglected one of the greatest mission fields at home:

One thousand dollars spend in any one of the seven States in which colored people live in great numbers will do more good than ten thousand dollars spent anywhere else on earth. Brethren, if it is the souls of men we are trying to save, why should we look to see what the color or the nationality of the man is? (Cassius, Nov. 23, 1915, 13).

Cassius’ outspokenness on the race issue won him friends but also created enemies. (Robinson, Trailblazer, 24). Yet he continued to preach and to goad his white brethren into aiding his efforts of evangelism to African Americans until his death in 1931.

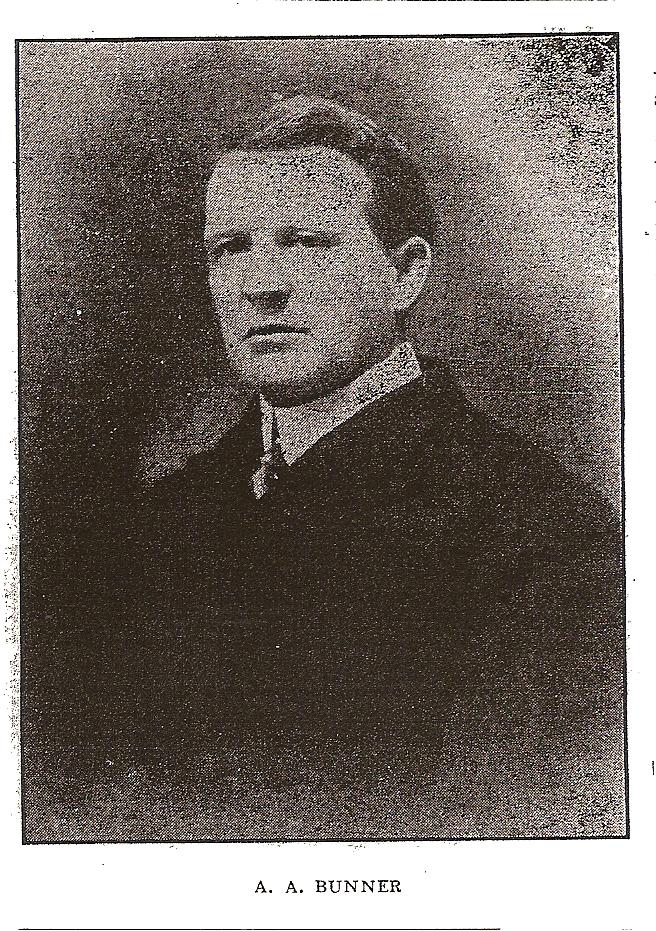

One of the friends that Cassius made among white brethren was A. A. Bunner. Bunner, a native West Virginian and itinerant evangelist in the Ohio Valley, spoke of the impression Cassius had made on him:

We all looked upon Bro. Cassius as one of the most humble, God-fearing men, either in white or black skin, we ever met. Bro. Cassius is doing a noble work, for it is the work of the Lord, among his race; and my prayer is that the churches everywhere will have liberal fellowship with him in this work of uplifting a persecuted and down-trodden race. (Bunner, Oct. 21, 1919, 9).

But Bunner was not content to just raise support for Cassius. He too was determined to speak out on the “race problem.” When he moved to Cleveland, Ohio to begin a new congregation, he spoke of a Bible reading series he had begun: “We hope in this series to Scripturally solve the Race problem. It can easily be solved by the word of God. We hope to prepare this effort for the press. I feel sure that I understand the subject and can present it from a Bible standpoint.” (Bunner, Dec. 12, 1921). Bunner was true to his word and put his study into print. He began by asserting the unity of all races since all are descendants of Adam. Bunner then discussed the curse of Canaan found in Genesis 9:18-27. Since the passage states that Canaan was the father of Cush (Ethiopia), the passage was often used to prove that the curse placed on Canaan was the origin of the black man. This passage was further used to support white racial superiority and black inferiority. Bunner confessed that he did not know if climate conditions or if the curse of Canaan had produced the physical differences between blacks and whites but he concluded “their physical differences from the white race were brought about through the overruling Providence of an all-wise God, who does everything for the best of his creatures. (Bunner, Race, 5). Since this was true, Bunner believed that no one had a right to question God’s decision, and white men needed to remember “I am my brother’s keeper.” As further proof of the unity of the races, Bunner stated:

The Negro is a creature and belongs to that part of creation that needs the Gospel, Mark 16;15, and the Church of Christ is under the same obligation to him that it is to any other creature who is a gospel subject, and we will be held to a strict account for withholding the Gospel from him. (Bunner, Race, 5. Italics in original).

In addition to demonstrating the unity of the races, Bunner also asserted the unity of the Church. This unity could not allow separate fellowships on the basis of race. “I know no white and colored churches of Christ.” (Bunner, Race, 6). Bunner stated that African-Americans were full-fledged citizens of America and entitled to all the rights of citizenship: education and due protection of the law. But they were also equal citizens in the kingdom of God.

. . . the same blood of the Lamb that frees us in Christ, frees them and gives them equal rights as citizens of the kingdom of God and heirs of heaven, and we must not respect the persons of men one above another, 2 Chron. 19:6,7; Rom. 2:11; Eph. 6:9; Col. 3:25; Jas. 2:3, 10; Prov. 24:23; 28:21. Read all of the above Scripture citations and then ask yourself the question, “Do they mean me?” (Bunner, 7).

Bunner did not hold back as he pointed out the meaning of 1 John 5:1:

Now, if I claim to be born of God and called to be a child of His, and there is a man with black skin, thick lips and kinky hair sitting by me who has been begotten and born of God, if I do not love that man as a brother and an equal heir with me to the same blessings and privileges of the Father’s family, this to me and to you and to all who understand and love God and respect His word is a sure evidence that I am not a child of God. (Bunner, 7).

Due to the two facts of unity of the human race and the unity of the Church, Bunner then affirmed:

Hence , I conclude that God has no black and white Savior. He has but the one and only Savior for all the race of men, and he saves all on the same conditions. He has no black and white churches, but he has but the one blood-bought Church, and it includes all nations in its folds. (Bunner, 7).

Bunner addressed the problem of separate fellowship between the races. But he also pointed out what prolonged separation could do:

While I do not object to the colored and white brethren meeting in separate congregations, as a matter of convenience and expediency, when they are so circumstanced that they can conveniently do so, still, if these separate congregations tend to create an ungodly race prejudice, then these separate meetings are sinful and destructive of the spirit of Christ and the unity that must exist among the people of God on earth, if we ever expect to enter heaven. “We be brethren in Christ.” (Bunner, 7-8. Italics in orginal).

Cassius and Bunner were willing to “cross the bridge” of segregation in their day. But they were people ahead of their time.

Despite the continued problems of prejudice and segregation, black congregations grew in the first half of the 20th century. Prior to the Civil War, there were few independent black congregations. In a 1990 Gospel Advocate article, James Maxwell listed three black congregations established before the Civil War. One was at Selina, Tennessee, another at Thyatira, Mississippi, and another at Ricks, Alabama.(Maxwell, 16). It is impossible to know with accuracy how many black congregations emerged in the second half of the 19th century. In 1895, the editor of the Christian Standard estimated that there were 45,000 members in 600 congregations. (Harrell, vol. 2, 201). The states with the largest numbers of black congregations were all in the South , led by Kentucky and Texas. The problem of accurately accounting of black congregations was exacerbated by the division which occurred in the Restoration Movement at the end of the 19th century over instrumental music and missionary societies. But out of that division came a congregation whose leaders would be instrumental for the growth of the gospel among African Americans and for challenging segregation in their own ways.

When the Lea Avenue and Gay street congregations in Nashville followed the Disciples of Christ by adopting instrumental music into their worship assemblies, S. W. Womack and Alexander Cleveland Campbell established a separate congregation, initially meeting in a house then moving to the student chapel of Fisk University. Later this property was purchased and became known as the Jackson Street Church of Christ. From this congregation in Nashville would come two outstanding black evangelists whose names were synonymous with the black churches of Christ, Marshall Keeble and G. P. Bowser.(Hooper, 259-260).

Marshall Keeble was the outstanding evangelist, black or white, of the first half of the 20th century. In many ways, his success was built on a foundation that S. R. Cassius had labored long to build. (Robinson, Samuel,24). Keeble’s efforts resulted in the baptism of more than 40,000 people in his lifetime and in the creation of more than 300 congregations throughout the nation. (Phillips, 317).

Keeble’s sermons were noted for their “spice.”(Glenn, 7). His way of illustrating his points through recounting his personal experiences and down to earth stories, helped Keeble’s audience to identify with him and accept his message. Keeble’s recurring theme was “the Bible is right.” “Make up your minds, the Bible is right. You can go home and fuss all night, the Bible is right. You can walk the streets and call Keeble a fool, the Bible is right. You can go home and have spasms, the Bible is right.” (Keeble, Biography, 46).

Most of Keeble’s work was concentrated in the South in the time of segregation and “Jim Crow” laws. As a result, Keeble had to walk a delicate line as he depended on white support while accommodating white segregation. (Robinson, Show Us, 74). Among the factors attributed by Keeble to his success was the interest and support white Christians had given to his evangelism. (Glenn, 7). Notable among white supporters for Keeble was Christian businessman A. M. Burton and B. C. Goodpasture, editor of the Gospel Advocate. This interest and support however, was tempered by white racism. Keeble “knew his place” and so he was supported. (Glenn, 7). But Keeble refused to look on his supporters critically. “Keeble never professed to see racism in white men’s words or events.” (Hooper, 265). This was true, even when he bore the brunt of vicious, violent attacks. In 1939, Keeble was holding a meeting in Ridgely, Tennessee. One evening, when the invitation was extended a white man came forward. Keeble leaned forward to take the man’s confession. Instead, the man struck Keeble in the left side of his head with brass knuckles. Keeble staggered under the blow as the man ran out of the assembly. (Choate, 78). Several of those in attendance urged Keeble to press charges against the man, but he refused to do so. Keeble’s attitude of forgiveness gained him acceptance in the whole community, black and white. While criticized for his accommodation to racial segregation, Keeble never believed that he compromised.

His humility was genuinely Christian. He was so deeply committed to the Christian principles of turning the other cheek, self-denial, cross-bearing, and suffering for righteousness’ sake that he was able to endure in silent uncomplaining resignation all the insults, indignities, threats, assaults, and racial slurs heaped on him. (Phillips, 318).

Keeble stood in the tradition of Booker T. Washington and had learned from his example. One time he said he had read Washington’s book “from lid to lid.”(Keeble, Godsend, xvii). Keeble’s feelings about racism and segregation, were rarely outwardly manifested.

Keeble’s work was extended through the many young men he mentored, through his personal example and later through the Nashville Christian Institute. “Marshall Keeble’s greatest legacy may well have been the company of spiritual sons he left behind who perpetuated his work of planting, edifying, and solidifying black Churches of Christ throughout the South.” (Robinson, Show Us, 137).

G. P. Bowser’s name is not as well known as Keeble’s among white churches of Christ, but his role in training future leaders in African American congregations was just as important. Bowser also approached race relations in a different manner than Keeble, which may account for his relatively obscure status among whites in comparison to Keeble. If Keeble stood in the tradition of Booker T. Washington, Bowser stood in the tradition of W. E. B. DuBois. DuBois openly criticized Washington’s approach to race relations. He advocated for equal rights and education of black leaders. While Washington and Keeble accepted white paternalism, DuBois and Bowser held white involvement in their work at arm’s length. (Hooper, 264-265).

G. P. Bowser

Bowser had received a theological education in a Methodist seminary. This first class training lifted him above many of his contemporaries, black and white. Bowser and his wife were baptized into the Gay street Christian church after Bowser’s quest for scriptural answers to his questions led him out of Methodism. Bowser also followed S.W. Womack and Alexander Cleveland Campbell when they left the Christian church over the use of instrumental music in worship and the missionary society. (Boyd, 23-26).

Two ideas persisted in Bowser’s ministry: use of the printed page and education. In 1902, Bowser bought a small hand press which he operated from his home. Bowser began the Christian Echo, a journal for black Churches of Christ. Through this medium Bowser was able to keep in contact with individuals and congregations among the black fellowship. Through the Echo, Bowser was also able to provide well written articles and studies which greatly benefitted others who did not have his educational achievements.(Boyd, 29)..

Bowser began the Silver Point Christian Institute at Silver Point, Tennessee in 1909. This community had relatively favorable relations between the black and white population and thus, the small community 75 miles east of Nashville, became the center for Bowser’s educational endeavors. (Boyd, 32-34). The Silver Point school was at its zenith in 1912. It made a lasting impact on many individuals in black churches of Christ. But financial difficulties were always the case, as at most other schools, black or white. Bowser grew increasingly discouraged over the lack of support for his school. He believed that white brethren were prejudicial in failing to support Christian education for black young people. (Boyd, 62-63). In 1918 Bowser resigned as principal of the school and it closed two years later.

But another opportunity came in 1920, as A. M. Burton planned on establishing a Christian school for blacks in Nashville. Burton purchased a building to house the school and invited Bowser to be principal. But Burton, wanting to gain white patronage and good will for the school, appointed C. E. W. Dorris as superintendent of the school. Dorris, a white preacher in Nashville, told Bowser and the students that they would have to enter by the back door to the school. Bowser was indignant and refused to give in to segregation in his own school. (Boyd, 66). Bowser left the school the same week and the school was closed.

Later, after preaching in Louisville, Kentucky for several years, Bowser went to Fort Smith, Arkansas where he established the Bowser Christian Institute in 1938 and continued to print the Christian Echo. Despite the sacrifices of Bowser and many black Christians, the school, started in the midst of the hardships of World War II, closed in 1946.(Boyd, 91-96). But its short life had a lasting impact through the development of four outstanding leaders in black churches of Christ – R. N. Hogan, J. S. Winston, Levi Kennedy, and G. E. Steward. (Hooper, 261). Bowser’s influence was also felt in the establishment of Southwestern Christian College in Terrell, Texas which opened in 1950.

Jack Evans, President of Southwestern Christian College gave this assessment of Keeble and Bowser.

These men preached the same gospel message, but differed greatly in their methods of presentation, in their philosophies about formal education, in the approaches to strengthening the churches among black people, and in relationships and dealings with white members of churches of Christ. (Hooper, 264).

By 1947, J.S. Winston estimated that there were 70,000 African-American Christians meeting in over 300 congregations. (Winston, 73). Keeble and Bowser were the catalysts for this growth.

The Civil Rights Movement

While Keeble, and to a lesser extent, Bowser had to accommodate themselves to racial discrimination in order to freely preach, their spiritual “sons and grandsons” were able to operate in a different era. (Robinson, Show Us, 172). The large numbers of African Americans who had served with distinction in the Armed Forces in World War II, helped to create a new mindset in the country. Following the war, the “color barrier” was broken in professional sports as Jackie Robinson and other players from the Negro Leagues moved into the previous all white Major Leagues. In the federal courts, laws of segregation were being challenged. The Supreme Court’s landmark decision in 1954 of Brown v. the School Board of Topeka, Kansas declared previous “separate but equal” rulings to be unconstitutional.

But as the Civil Rights movement began in the 1950’s and ushered integration in the nation, the deep racial divide within churches of Christ remained. African-Americans within churches of Christ labored mightily for the rights that they had been denied. For them, the gospel carried a community or civic responsibility as much as an individual responsibility. Whites within churches of Christ, with a few exceptions, were slow to raise their voices in support of equal rights and justice as they separated salvation from any social obligation. Many whites were unaware of the conditions of life for blacks with whom they had little social interaction. When whites did respond, their efforts were often only half-way measures.

One of Marshall Keeble’s “boy preachers” was at the center of the Civil Rights movement. Fred Gray had determined to become a lawyer and had secretly pledged to use the law to “destroy everything segregated I could find.” (Gray, 19). Gray became the attorney defending Rosa Parks in the Montgomery Bus Boycott. This catapulted Gray into the national spotlight and in a legal career where he was an attorney for Martin Luther King, Jr., successfully argued a landmark case before the Supreme Court on U.S. voting rights law, and helped to organize the 1965 Selma, Alabama march.

R. N. Hogan, successor to G. P. Bowser as editor of the Christian Echo, relentlessly challenged the racial segregation in Church of Christ related schools and congregations. Hogan took his cue on the sinfulness of racism from James 2:9. He stated, “It is my personal observation that most of our Brethren who are in high places in the church of our Lord, are going to lose their souls because they are respecters of persons.” (Robinson, Fight, 129). Hogan pointed out the hypocrisy of the segregated policies at Church of Christ schools that continued into the 1960’s.

One of our Ministers graduated from T. C. U., a Christian Church school, but he couldn’t go to Abilene Christian College. However, Bro. Figueroa of Mexico graduated there. Negroes are admitted to the State school at Fayetteville, Ark., but they cannot enter Harding College, a Christian (?) school. They are admitted in State supported schools in Tennessee, but he cannot attend David Lipscomb College in Nashville, Tenn., nor Freed-Hardeman College in Henderson, Tenn. If these schools will disassociate the name Christian from them, their practice would not reflect so badly on the Cause of Christ. (Robinson, Fight, 130).

Other outspoken critics of the segregation existing in churches of Christ were Roosevelt Wells and Franklin Florence. (Hughes, 303-305).

If the 1960’s were the most turbulent decade of the 20th century in United States history, it would never be known from reading white journals of churches of Christ. The pages of the Gospel Advocate, Firm Foundation, and other publications were virtually silent on the social issues of the period. (Hughes, 284). This silence and lack of support for the cause of civil rights contributed to the alienation of race relations within churches of Christ. Blacks viewed the silence of whites as ignorance at best and racist at worst. But there was more than racism contributing to the silence of whites during the civil rights movement.

The powerful influence of David Lipscomb’s view of civil government was a factor in keeping many whites from speaking out on social and political issues. Lipscomb viewed all human governments as being at war with God’s rule. Lipscomb held that Christian participation in human governments should be limited to prayer , the payment of taxes, and obedience to the law as long as it was not in conflict with the law of God. Because of this limitation, Lipscomb urged Christians not to be involved in politics or to vote. (Lipscomb, Civil Government, 145). This legacy of non-involvement in civil affairs and politics led many in churches of Christ to disparage those who were active in civil issues as proclaiming a “social gospel” and abandoning the gospel of Christ.

Submission to authority (Rom. 13:1-7; 1 Pet. 2:17) has always been a part of the doctrine of Christ that has historically inhibited Christians from participation in revolution against government. For many white Christians, as they observed a decade of protest marches, race riots, and assassinations, the social activism of the civil rights movement was viewed as violent revolution rather than peaceful demonstration. Note how Marshall Keeble was eulogized in the Gospel Advocate following his death which occurred in the same month that Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. “He never led a march or a demonstration, peaceful or otherwise. He was never connected with a riot.” (Goodpasture, 449).

But there were a few white voices raised against the injustices and inequalities of society and in the churches. In 1953, Everett Ferguson made a chapel talk on race relations at Abilene Christian College. Ferguson stated,

As Americans, citizens of a democracy, we give lip service to the principle that all men are created equal – not an arbitrary equality, but equal as to rights and opportunities. Yet, in daily living we deny equal rights and equal opportunity to a large segment of our populations. (Ferguson, 1).

Ferguson stated that there was no basis for race prejudice in Scripture as he cited Acts 17:26; Romans 2:11; Galatians 3:28; and Colossians 3:11. But Ferguson decried efforts at legislating equality. He pointed to the letter of Philemon as indicating that Christianity “did not work for radical change in the social structure” but within existing social framework. Ferguson argued that prejudice cannot be legislated away but must be overcome through education. (Ferguson, 2-3). But there were few supporters of Ferguson’s call to voluntarily integrate ACC.

In 1957, as desegregation was being enforced at Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, some Harding College students began to call for integration of their campus. But Harding president, George S. Benson, was as deeply committed to conservative American politics as he was to Christianity. Benson defended “the American Way and the status quo of racial segregation to the hilt.” (Brown, 3). Led by student association president Bill Floyd and supportive faculty members, a “Statement of Attitude” was put forth to indicate student support for integration. The statement read:

A number of members of the Harding College community are deeply concerned about the problem of racial discrimination. Believing that it is wrong for Christians to make among people distinctions that God has not made, they sincerely desire that Harding College make clear to the world that she believes in the principles of the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man. To that end, the undersigned individuals wish to state that they are ready to accept as members of the Harding community all academically and morally qualified applicants, without regard to arbitrary distinctions such as color or social level; that they will treat such individuals with the consideration and dignity appropriate to human beings created in the image of God; and that they will at all times face quietly, calmly, patiently, and sympathetically any social pressures intensified by this action. (Brown, 5).

Despite the fact that nearly 75% of the students, faculty, and staff had signed the statement, Harding’s policy did not change. George Benson and Harding’s Board of Trustees refused to risk that they would lose some students and lose “much standing in the community – a community not yet ready” for integration. (Brown, 4).

Carl Spain’s lecture at Abilene in 1960, explosively challenged a mindset that was content to wait for slow change in race relations. Spain said, “We fear the mythical character named Jim Crow, more than we reverence Jesus Christ.” (Robinson, Fight, 132). He went on to indict the blatant racism he encountered.

I feel certain that Jesus would say: ‘Ye hypocrites! You say you are the only true Christians, and make up the only true church, and have the only Christian schools. Yet, you drive one of your own preachers to denominational schools where he can get credit for his work and refuse to let him take Bible for credit in your own school because the color of his skin is dark!’ (Hughes, 290).

Spain’s lecture received broad support and prompted rapid action as Abilene Christian began admitting black students the next year. Other Christian colleges within churches of Christ followed suit over the next several years.

Race Relations Today

The struggle of race relations in the Restoration Movement continues to mirror the struggle of race relations in the nation at large. The election of the nation’s first black President and the improved legal and economic conditions of African-Americans have made for better appearances in race relations, but prejudice and racism still lie beneath the surface. Someone has called American Churches as “the most segregated places in America.” While the statement may be too broad, considering the number of private institutions in the country, nevertheless, many Churches, including churches of Christ, fit the description. As the country wrestles with race relations along with additional burdens of national security and immigration issues, addressing prejudice and racism is a continuing priority.

This study suggests several things that need to be implemented in order to improve race relations among churches of the Restoration plea. One thing that is demonstrated is that far too often, the churches of the Restoration movement conformed to society rather than challenged it. This failure to be salt and light (Matt. 5:13-16) renders Christians useless in their calling.

In order to be living sacrifices, each Christian must have a renewal of the mind by the doctrine of Christ (Rom. 12:1-2). This doctrine affirms creation, and the equality of all nations. “. . . since He gives to all life, breath, and all things. And He has made from one blood every nation of men to dwell on all the face of the earth, . . . “ (Acts 17:25-26).

The doctrine of Christ is about salvation. The saving sacrifice of Christ is for all men (John 3:16; 1 John 2:2). The gospel message is a message of salvation for all nations (Matt. 28:19; Rom. 1:16). The gospel message proclaims the oneness in Christ (Gal. 3:28), and breaks down walls of separation (Eph. 2:14-18).

The doctrine of Christ also instructs the citizens of the Kingdom of God to live by differing values. As kingdom people, we must learn to replace hatred with love (Matt. 5:21-22). Seeing that our relationship to God is demonstrated in our relationship to our fellow man (1 John 4:20-21), each Christian must take the initiative of reconciliation (Matt. 5:23-26; 2 Cor. 5:17-20). Each citizen of the kingdom is to reflect and model the love of the Father (Matt. 5:46-48). In addition to loving those we would love to hate, this means that we learn to love those we would hate to love. Who do you have over for meals? Who do you want to be seen with?

Kingdom people must also refuse to make harsh, censorious judgments of others (Matt. 7:1-5). This would include the prejudice and stereotyping of racism. While all Christians must practice spiritual discernment (Matt. 7:6, 15-20), the golden rule of the kingdom is to treat others in the way we would want to be treated (Matt. 7:12).

Eschatology is another facet of the doctrine of Christ that should bring about transformation of Christians and defeat racist and prejudicial thinking. In heaven, there will be no black fellowship or white fellowship. There will only be the fellowship of the redeemed. (Heb. 12:22-24; 2 Pet. 3:10-14). In heaven, there will be no back door entry or “back of the bus” seating. In heaven, there will be no “whites only” signs. In heaven, there will be no need for separate fellowships because we are afraid of giving up power. “Every knee should bow, of those in heaven, and of those on earth, and of those under the earth, and every tongue should confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.” (Phil. 2:10-11). If such will be the case in heaven, should we not work to make this a reality in the kingdom now? If we do not, is this an indication that we may numbered among the goats and not the sheep in the great day of judgment? (Matt. 25:31-46).

There are practical steps that can be made in improving race relations between black and white congregations. The apostle Peter wrote saying, “Love the brotherhood.” (1 Pet. 2:17). In order to love the brotherhood, we must first know the brotherhood. To live in separate fellowships, with very little interaction among us, is to give fertile ground to ignorance which fosters prejudice and racism. Greater communication with one another can increase our understanding of one another. We must learn to engage in courageous conversation with one another.

The example of Paul is helpful in understanding how to apply these principles. Paul was a chosen vessel to the Gentiles (Acts 9:15). This man steeped in the traditions of Judaism believed he could do the impossible through Christ (Phil. 4:13). As such a believer, he became “all things to all men, that I might by all means save some” (1 Cor. 9:19-22). This was not shabby compromise with the world, but the way of crossing cultures for sharing Christ.

There will probably always be black churches and white churches due to our weaknesses. But where there are congregations that can be integrated, it must be done out of a spirit of equality, not just paternalism or tokenism. Blacks and whites should share in leadership. If congregations are large enough for more than one preacher, it would be wise to have preachers from both groups. Wisdom and care must be exercised in all facets of ministry to ensure that no charges of neglect could be made (Acts 6:1).

As David Lipscomb said so clearly long ago, “The only point really involved in this difficulty is, whether we will be led by the Spirit of Christ and the teachings of the Bible, or by our prejudices against the negro.” The choice is ours.

Appendix Study - Slavery in the New Testament

As is demonstrated in the writings of those who defended slavery in America, an appeal was made to the New Testament for support of their practice. Passages like Ephesians 6:5-6, Colossians 3:22- 4:1 and the little book of Philemon were held as proof that the American situation was approved by God. But there were significant differences in the practice of slavery as found in the New Testament and its practice in America. In order to prevent misuse of the Scriptures in the aid of prejudicial and racist practices, note some of these differences.

There were over 60 million slaves in the Roman Empire, with slaves greatly outnumbering free persons. An individual became a slave through a variety of circumstances. Conquered people became slaves in war. Some individuals became slaves due to poverty, as they became so indebted, the only way the debt could be paid was to sell themselves into slavery. Some people were born into slavery. Some slaves even owned slaves! Slaves were viewed as a part of the extended Roman household, hence the New Testament instruction regarding masters and slaves is found in contexts addressing the Christian home. Slavery in the time of the New Testament knew no racial or ethnic boundaries. A black man could own white slaves, something that would have never happened in America. Slavery in New Testament times was harsh and cruel. A slave was regarded as chattel property and not as a person.

New Testament instructions to slaves as well as masters were made to prevent violence and bloodshed, and to limit cruelty, but not to endorse the institution of slavery. As Jesus told Pilate, His kingdom is not of this world. (Jn. 18:36). Christ’s life and His teachings were the leavening power permeated with love that eventually transformed the cruelties of Roman society and ended slavery. Early Christians used their funds to buy slaves and set them free.

May God help us to correctly handle His word. (2 Tim. 2:15).

Appendix II – Scriptures Used by the Restorers in this Study

|

Men and their Scriptures opposing Slavery and Segregation |

Men and their Scriptures defending Slavery and Segregation |

|

Stone - Ps. 85:10; Matt. 19:29 |

Campbell, Shannon – Eph. 6:5-9; Col. 3:22-4:1; Philemon |

|

Campbell – Rom. 6:16; Prov. 14:34; 1 Cor. 7:20-21 |

1 Cor. 7:20 |

|

Abolitionists – Matt. 7:12 |

|

|

David Lipscomb – Gal. 3:28; Matt. 25:40 |

S. E. Harris – 1 Cor. 8:13 |

|

Rebuttal of Harris – Gal. 2:5 (example of Titus) Luke 17:2 |

|

|

Bunner – Gen. 9:18-27; 2 Chron. 19:6-7; Rom. 2:11; Eph. 6:9; Col. 3:25; Jas. 2:3, 10; Prov. 24:23; 28:21; 1 John 5:1; |

|

|

Hogan – Jas. 2:9 |

|

|

Ferguson – Acts 17:26; Rom. 2:11; Gal. 3:28; Col. 3:11 |

Ferguson – Philemon |

Works Cited

Boyd, R. Vernon. Undying Dedication: The Story of G. P. Bowser. Nashville, TN: Gospel Advocate, 1981.

Brown, Michael D. “Despite school sentiment, Harding’s leader said no to integration” Arkansas Times, Jun 6, 2012. http://m.arktimes.com/Arkansas/despite-school-sentiment-hardings-leader-said-no-to-integration. Accessed 6-7-2012.

Bunner, A. A. The Race Problem – Historically and Scripturally Solved, with Special Reference to the Negro Race and the Church’s Attitude Toward Them. Nashville, TN: Williams Printing, 1922.

___________. “Gospel Flashlights,” Christian Leader Oct. 21, 1919:9.

___________. “Field Reports – Cleveland, Ohio,” Christian Leader Dec. 27, 1921: 12.

Campbell, Alexander. “Emancipation of White Slaves,” Millennial Harbinger vol. 1 no. 3 (March 1830): 128-132.

___________. “The Crisis,” Millennial Harbinger vol. 3 no. 2 (February 1832): 86-93).

Cassius, S. R. “Among Our Colored Disciples,” Christian Leader April 5, 1904:4-5.

__________. The Third Birth of a Nation. Cincinnati: F. L. Rowe Publishing, 1920.

____________. Negro Evangelization and the Tohee Industrial School. LaVergne, TN: Kessinger Publishing, 2009 reprint of 1898 original.

Choate, J. E. Roll Jordan Roll: A Biography of Marshall Keeble. Nashville, TN: Gospel Advocate, 1968.

Daugherty, Bruce E. “Views on Race Relations in the Christian Leader from 1914-1938” Restoration Quarterly, vol. 49 no. 1 January 2007: 39-49.

Ferguson, Everett. “Race Relations” Chapel Speech delivered at ACU, spring/fall 1953. ACU Center for Restoration Studies. http://www.bible.acu.edu/crs/ItemDetail.asp?Bookmark=1588. Accessed 6-17- 2014.

Gibbs, G. F. “A Plea for the Carolina Negro,” Christian Leader June 9, 1926: 3.

Glenn, E. H. “Keeble in California,” Christian Leader May 16, 1933: 7.

Goodpasture, B. C. “The Special Keeble Issue” Gospel Advocate vol. 110, no. 29, July 18, 1968.

Gray, Fred D. Bus Ride to Justice – Changing the System by the System. Montgomery, AL: The Black Belt Press, 1995.

Hale, Jess O. Jr. “Ecclesiastical Politics on a Moral Powder Keg: Alexander Campbell and Slavery in the Millennial Harbinger, 1830-1860” Restoration Quarterly vol. 39 no.2 :65-81.

Harrel, David E. Jr. Quest for a Christian America, 1800-1865 – A Social History of the Disciples of Christ, vol. 1. Tuscaloosa, AL: The University of Alabama Press, 1966.

_______________. Sources of Division in the Disciples of Christ: 1865-1900 – A Social History of the Disciples of Christ, vol. 2. Tuscaloosa, AL: The University of Alabama Press, 1973.

Haymes, Don, Eugene Randall II, and Douglas a Foster. “Race Relations” in Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement, Douglas A. Foster, Paul M. Blowers, Anthony L. Dunnavant and D. Newell Williams eds. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing, 2004:619-622.

Hooper, Robert E. Crying in the Wilderness: A Biography of David Lipscomb. Nashville, TN: David Lipscomb College, 1979.

_____________. A Distinct People. West Monroe, LA: Howard Publishing, 1993.

Hughes, Richard. Reviving the Ancient Faith. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing, 1996.

Keeble. Marshall. Biography and Sermons of Marshall Keeble, B. C. Goodpasture, ed. Nashville, TN: Gospel Advocate Publishing, 1931.

_____________. A Godsend to His People: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Marshall Keeble. Edward Robinson, ed. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 2008.

Lard, Moses. “The Work of the Past – The Symptoms of the Future” Lard’s Quarterly vol. 2 no. 3 (April 1865): 251-262.

Lipscomb, David. Civil Government. Nashville, TN: McQuiddy publishing, 1913.

____________. “The Negro in the Worship – A Correspondence,” Gospel Advocate vol. 49 July 4, 1907: 424-425.

____________. “The Negro in the Worship.” Gospel Advocate vol. 49 August 1, 1907: 488-489.

_____________. “The Negro in the Worship.” Gospel Advocate vol. 49 August 15, 1907: 521.

Lunger, Harold K. The Political Ethics of Alexander Campbell. St. Louis: The Bethany Press, 1954.

McAllister, Lester. Thomas Campbell: Man of the Book. St. Louis: Bethany Press, 1954.

Maxwell, James O. “The Restoration Movement,” Gospel Advocate (January 1990): 15-16.

Phillips, Paul D. “The Interracial Impact of Marshall Keeble, Black Evangelist 1878-1968” in The Stone-Campbell Movement. Michael W. Casey and Douglas A. Foster, eds. Knoxville, TN: The University of Tennessee Press, 2002: 317-328.

Poyner, Barry C. Bound to Slavery – James Shannon and the Restoration Movement. Fort Worth, TX: Star Bible Publications, 1999.

Richardson, Robert. The Memoirs of Alexander Campbell, vols. 1 & 2. Cincinnati: 1868.

Robinson, Edward. “The Two Old Heroes: Samuel W. Womack, Alexander Campbell, and the Origins of Black Churches of Christ in the United States” Discipliana, vol. 65, no. 1 Spring, 2005: 3-20.

______________. “Samuel Robert Cassius: A Forgotten Trailblazer in Churches of Christ” Restoration Quarterly vol. 48, no.1 January 2006: 11-24.

______________. To Save My Race From Abuse. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 2007.

______________. Show Us How You Do It. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 2008.

_____________. The Fight is On in Texas. Abilene, TX: Abilene Christian University Press, 2008.

Shaw, Henry K. Buckeye Disciples. St. Louis: Ohio Christian Missionary Society, 1952.

Stone, Barton W. “An Humble Address to Christians, on the Colonization of Free People of Color,” Christian Messenger vol. 3 no. 8 (June 1829): 198-200.

_____________. “Liberia,” Christian Messenger vol. 7 no. 2 (February 1833): 62-64.

_____________. “Editorial,” Christian Messenger vol. 7 no. 8 (August 1833): 244.

Winston, J. S. “Work Among the Colored People in the U. S.” in The Harvest Field, Howard L. Schug and Jesse P. Sewell, eds. Athens, AL: Bible School Bookstore, 1947.

West, Earl I. The Search for the Ancient Order, vol. 1. Nashville, TN: Gospel Advocate Co., 1974.

__________. The Search for the Ancient Order, vol. 3. Indianapolis, IN: Religious Book Service, 1979.

__________. Trials of the Ancient Order. Germantown, TN: Religious Book Service, 1993.

__________. The Life and Times of David Lipscomb. Germantown, TN: Religious Book Service, 1953.