Views on Being a Distinct People

(Relations to the World, Denominations, and Apostates)

by Bruce Daugherty

James A. Harding has been called the “gracious separatist.” (Hicks, 129). He believed that the inclusiveness of Christ involved an exclusiveness. “If you are in Christ Jesus you must be separated from those who are out of Christ.”(Harding, 178). His separatism drew a line between the Church and the world, between the Church and the denominations, and between the faithful and apostates. But there was a tension in Harding’s separatism as he recognized one could become sectarian while “opposing sectarianism.” (Hicks, 137).

J. A. Harding

J. A. Harding Did the editors of the Christian Leader share this vision of separation from the world? This study will seek to answer this question by examining Leader articles urging separation from the world, separation from denominations and their methods, articles dealing the Christian Church and articles addressing the tension of becoming sectarian while making a non-sectarian plea.

The pleasure pursuits in the “roaring twenties” made separation from the world difficult. C. D. Moore listed the pleasures engaged in: “playing pool, euchre, poker, and such like games, and basketball, football, and baseball, and attend the movies and other theatres . . .”. Moore preached against these practices as things “of the flesh and of the world, and are carnal.” (Moore, 16). S. R. Cassius condemned the “movie, soft drinks, and short skirts.” Cassius saw these things as undermining the “morals, health, and modesty” of those who indulged in them.(Cassius, 8). Since Christians were to be a “chosen generation, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a peculiar people” (1 Pet. 2:9), with a “citizenship in heaven” (Phil. 3:20), they needed to observe the spiritual boundary lines that God had made for His kingdom on earth.

But what of individuals who believed they were saved, yet found themselves in denominations? Ira Moore answered the question: "Every sectarian or denominational system has some Christianity in its teaching; but there is no sectarian system which, when believed and obeyed, will make Christians. People may, in spite of all such systems and teaching, become Christians by believing and obeying the Gospel. And, like any other Christian, go wrong by becoming identified with an unscriptural body and fail to practice Christian duties and discharge Christian obligations. That kind needs to heed the call to those in Babylon to “Come out of her my people.” (Moore, 1925, 4).

Moore also explained that Mark 9:38-40 did not give sanction to denominations. To apply this passage and its instruction, “forbid him not,” to denominational division and practices was a misuse of the passage. Moore pointed out the differences between denominations and the passage in Mark. "John acknowledges that the one they saw casting out demons was doing it 'in the name of Christ,' which means by Christ’s authority. People do not form denominations by the authority of Christ; for he prayed that 'all that believe on me through their word might be one'(John 17:20,21)." (Moore, 12-1925, 4).

T. Q. Martin

In light of this separation, T. Q. Martin decried those who adopted worldly ways for evangelism. For Martin, to copy the denominations for the sake of “numbers” was to lose sight of the importance of loyalty to God and His way. The sectarian bodies were numbers driven. "In the world today there are numbers of religious bodies, each seeking to outstrip the others in numbers. And inasmuch as the spirit of self-denial has never been very popular, it happens that the more of the world, the flesh and the evil we adopt, the better will be the prospect for numbers." (Martin, Quantity, 5). But this was not the only form of worldliness holding back the Church in Martin’s view: "Various forms of worldliness are greatly hindering the Church today. There are those who have not adopted the carnival or other fleshly means for raising money or carrying on the work of the Church, but who are pouting or sulking or quarreling. See,

this is of the world. And so I repeat, different forms of worldliness are holding back the work of the Church." Martin encouraged readers to be motivated by no other desire than to glorify God.

The Lausanne Conference on Faith and Order in 1927 prompted Ira Moore to address its purpose. After reading George Klingman’s review of the conference, Moore believed it “may result in good and may not.” (Moore, Lausanne, 4). If the conference made a plea and defense of the “primitive faith and order” Moore believed it would result in good. But if the conference was just to “make each and all others feel confident they were absolutely right in their ‘faith and order,’ it matters not what it is, they are but working evil to all who come under their influence.” Moore asserted, that what was needed was the “faith and order inaugurated and established by the Son of God” and revealed in the “faithful preaching of His ambassadors.” A faith that is not created by the word of the Lord is not the “one faith” that is Divinely approved. One great barrier to the unity that should exist among religious people is that they have so much faith that is not made by “hearing the word of God.”

Denominational thinking was not confined to religious outsiders. T. Q. Martin believed that J. D. Tant’s familiar phrase, “we are drifting” rung true. Martin raised a warning to those who were careless or untaught concerning the line of separation between the Church and denominations. "Young people are growing up without a knowledge of the difference between denominational and undenominational Christianity. It may be a question as to how much denominational paraphernalia a congregation may have before it becomes a denomination, but there is no question as to the absolute safety in becoming, being and believing and doing just what the New Testament requires." (Martin, Lifting, 5). The solution was not to hastily condemn members for “failing simply to observe the customs to which we have been used.” This was to go to the opposite extreme. The solution was to be found in “much study of the word of God, patience, long-suffering, forbearance and love.”

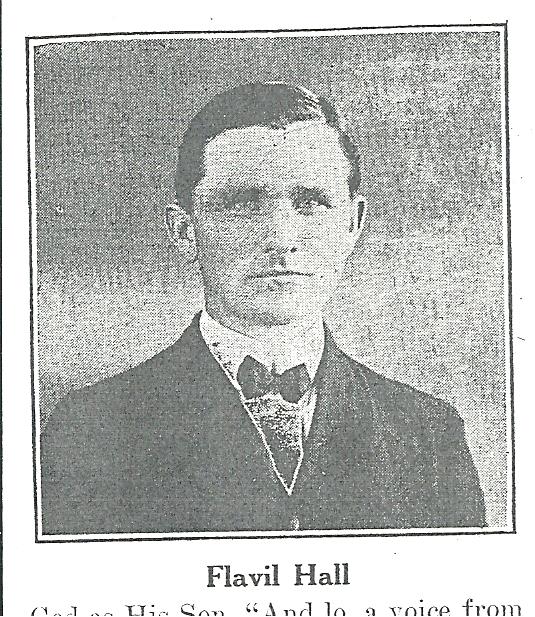

Flavil Hall was asked to explain 1 Corinthians 9:19-22 for some of his readers who were using the passage to defend the wearing of titles like “pastor” and participating in “union meetings.” Hall denied that this passage gave sanction to the adopting of worldly ways in order win souls. "Some have seized upon these words of Paul to justify Christians in conforming to the worldly fashions and follies of the religious and irreligious peoplearound them. No greater perversion of language was ever accomplished." (Hall, 1915, 10). Hall declared that the apostle Paul, who had suffered so much for his preaching Christ (2 Cor. 11:24-27), would not have sought worldly ease by doctrinal or moral compromise.

The bitter split with the Disciples of Christ prompted several articles in the period dedicated to stating the differences between the “faithful and the apostates.” In addition, there were articles aimed at helping the “faithful” defend their positions. But there were also articles made in a sincere appeal for brethren to return to formerly held beliefs. Several preachers and even a few congregations responded to the appeals in the period as they renounced their Disciples’ ties and declared their departure from apostasies. Hall L. Calhoun was the most renowned preacher to make the change.*

The difference between the two fellowships hinged on differing interpretations of Thomas Campbell’s famous slogan, “Where the Bible, speaks we speak; where the Bible is silent, we are silent.” Was Biblical silence permissive or prohibitive? Liberal Disciples like J. H. Garrison held a view that said "where the Scriptures were silent, they claimed the right -- indeed the duty -- to use 'sanctified common sense' and to follow 'enlightened judgment'." (McAllister and Tucker, 238).

C. G. Vincent shared with Leader readers an interesting article that Isaac Errett had written in the Christian Standard in the debate over instrumental music. In 1866, Errett declared that the famous motto had “met its Waterloo.” But despite Errett’s assertion, Vincent pointed out that the motto was still valid. He pointed to the inconsistency of the Disciple's reliance on silence as being permissive. Vincent said that the Disciples drew lines of fellowship over infant baptism and other practices. Vincent went on to point out that Errett’s understanding of the motto made silence as authoritative as a “thus says the Lord.” To Vincent, this was a turning away from sound hermeneutical practices. He stated: "Whatever is not required by commandment or approved example is not authorized, and hence should be left out. We should confine faith and practice to the expressed will of God. That is the meaning of the SILENCE of the Scriptures.” (Vincent, 2-3). Vincent detected a flaw in Errett’s reasoning. Errett’s answer to those who opposed the instrument was to equate all innovations. Religious newspapers, meeting houses, songbooks, and tuning forks were innovations on which the Bible was silent, but Christians utilized. Vincent pointed out that the problem was not with innovations, per se. "We should bear in mind, of course, that an ‘innovation,’ being something new, is not necessarily a violation of Bible teaching; but any innovation that does corrupt the worship or changes the acts of worship, their nature or that takes away from the church the work divinely assigned to it is sinful and this is what faithful brethren object to."

But in their opposition to the sects, had the Leader editors and writers become sectarian? Ira Moore defended his use of the designation, “Church of Christ.” "When I write “Church of Christ,” I am not attempting to say who belongs to it. I mean all the “called-out” ones. There are many who have not heeded the call to come out of sectarian errors and fellowship. (Moore, 12-1924, 4).

In an article following up on the idea of being non-sectarian, Flavil Hall lamented the fact that the teaching of F. D. Srygley had been so soon forgotten. "It was the dominant effort of the lamented F. D. Srygley from 1889 to the time of his death in 1900 to make it understood that anything smaller than all the saved (baptized, penitent believers who are endeavoring to be faithful to Christ) and at the same time larger than a local congregation is anti-scriptural and sectarian. (Hall, Don't Know, 6). Hall pointed out that the mentality of defining oneself by what one opposed had a negative effect on the non-sectarian plea. "Disciples, loyal at heart, have so long thought of themselves as belonging to the particular class of baptized believers who oppose instrumental music in the worship and church societies and as having no connection with baptized believers in what they call the 'Christian Church' that they were not prepared for anything to the contrary, so are saying, 'I don’t know where I am'.” To help his readers think differently, Hall held up the life of George Muller as an example of one to whom he would extend fellowship. (Hall, Faith, 1925, 5). After sharing some highlights from Muller’s biography, Hall declared, “If Muller, in any sense belonged to a human denomination he rose above the spirit of sectarianism and sought to obey and serve the Lord according to the Bible.” Hall did not endorse every view of Muller’s as being biblical but he was glad to think of Muller as a brother. For Hall, such thinking should not deter one from warning others against the dangers of the sects, just like non-sectarians should be warned against the dangers of worldliness.

But some of the Leader readership had a hard time with Hall’s extension of fellowship to individuals like Muller or Charles Spurgeon. Tice Elkins believed Hall’s statements to “be of great comfort to almost all sectarians if they were to read it.” Elkins viewed Muller and Spurgeon as preachers who were “converted to doctrines not found in the word of God, and they did not preach the word of God.” Elkins believed he would be guilty of misleading others if he preached “honest endeavors” as placing them in the Church of Christ, rather than submission to the gospel as revealed by the Holy Spirit.(Elkins, 7). In an article defending his fellowship of Muller, Hall listed some of Muller’s beliefs as given in Muller’s biography. Hall then compared them to some of the beliefs of Barton W. Stone. If brethren were willing to look on Stone as a pioneer in breaking away from sectarianism despite the fact that Stone held to some un-orthodox views until his death, Hall argued that they should look at Muller in the same light. (Hall, Did Not, 5).

While separation from denominations and the world was necessitated by fellowship with Christ, unity in Christ was not forgotten by the publisher and editors of the Christian Leader. The period saw several unity initiatives.

The Murch-Witty meetings of the late 1930's were the most publicized and attended discussions aimed at unity. The meetings grew out of correspondence between James DeForest Murch of the Christian Church and Claud F. Witty, minister for the Central Church of Christ in Detroit, Michigan.(Murch, 126). From the discussion between the two men came a series of conferences in 1937 attended by other preachers and interested parties. This resulted in a “National Unity Meeting” held May 3-4, 1938 in Detroit, Michigan. The format for these meetings was more conducive to dialogue than to debate, as it sought to emphasize the things held common in faith and practice.

But for some brethren this was precisely the problem. Ira Moore had seen many “unity meetings” proposed through the years and he didn’t see the Murch-Witty initiative as proposing anything new. "As has been stated in these columns before, writers on unity erect a wrong standard to which to invite the people. . . . just an agreement to disagree and each maintain his “tribal identity.” To agree with the Apostles of the Lord and be in unity with them is left out of the consideration." (Moore, Evidently, 4). Unity on this basis was disloyalty to the unity “plan” given in the New Testament. Quoting 1 John 1:3-4, Moore argued, “What they (the Apostles) have written, then, contains ‘the plan’ for the unity for which Jesus so earnestly prayed.”

D. H. Hadwin

D. H. Hadwin also had little faith that the meetings would accomplish good. Hadwin had been an ordained minister in the Christian Church for eleven years before leaving their fellowship to preach for the church of Christ meeting in Shadyside, Ohio. Hadwin believed he had left apostasy to return to the truth. He was a personal friend of James D. Murch, but he turned down Murch’s invitation to participate in the unity meetings. Hadwin believed that there was “more danger of harm than good in such meetings.”(Hadwin, 6). I would not be so alarmed were it not for the fact that the Christian Church is becoming more liberal instead of more conservative. In such fellowship meetings as those reported in the editorial under consideration, our brethren may find the fellowship of the representatives of the Christian Church so pleasant that they may be tempted to compromise with them. That is the danger."

Despite several strong editorials from Moore and others, Fred Rowe gave his support to the unity meetings. As well as carrying the announcements of the dates and times for the various meetings, Rowe issued a special double edition of the Christian Leader on March 1, 1938 dedicated to the theme of unity. The edition was ironic as it also carried memorial tributes to Ira Moore, long an opponent of the unity meetings, who had passed away on February 18.

In final analysis of the Murch-Witty efforts, no large scale outward unity was achieved between the two fellowships. In the autonomous arrangement of the congregations, individuals can meet together and influence others, but no representatives can make unity or decide policy for an entire fellowship. But some believed that it was better for them to have tried and failed than not to have tried. Years later, Murch gave this assessment of the reception of the meetings: "Among the more conservative periodicals of the churches of Christ, only the Christian Leader and the Word and Work were openly friendly. The Gospel Advocate was at first violent in its oppostion, but later joined with the Firm Foundation in studiously ignoring the movement." (Murch, 129).

Leader writers and editors in the period spoke of the consciousness of being a “distinct people,” which was reflected in separation from the world and from denominational bodies. This “called out” separation was especially maintained toward those of the Christian Church who were viewed as having departed from the faith. There is evidence that some people had become sectarian in their attitudes, primarily resulting from an identity defined by what it opposed. But for the majority of writers, unity at the expense of their separateness in Christ was undesirable.

Works Cited

Cassius, S. R. "Movie, Soft Drinks, and Short Skirts," Christian Leader 8-30-1927, 8.

Elkins, Tice. "I Do Know Where I Am," Christian Leader 4-23-1929, 7.

Hall, Flavil. "Field Notes and Helpful Thoughts," Christian Leader 1-26-1915, 10

__________. "Soulful, Hopeful, and Helpful Thoughts - Don't Know Where I Am," Christian Leader 4-2-1929, 6.

__________. "Soulful, Hopeful, and Helpful Thoughts - Faith, Prayer, and Trust," Christian Leader 4-16-1929, 5.

__________. "Soulful, Hopeful, and Helpful Thoughts - Did Not Feed in a Sectarian Pasture," Christian Leader 5-7-1929, 5.

Harding, James A. "A Much Neglected Doctrine," Gospel Advocate 3-23-1887, 178.

Hicks, John Mark. "The Gracious Separatist: Moral and Positive Law in the Theology of James A. Harding, " Restoration Quarterly, vol. 42 (2000), 129-147.

McAllister, Lester G. and William E. Tucker. Journey in Faith - A History of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). St.Louis: The Chalice Press, 1975.

Martin, T. Q. "Quantity or Quality?" Christian Leader 10-20-1925, 5.

_________. "Lifting Up the Danger Signal," Christian Leader 7-16-1929, 5.

Moore, C. D. "Sword Swipes," Christian Leader 3-8-1921, 16.

Moore, Ira. "Editorial Views and Reviews," Christian Leader 12-2-1924, 4.

_________. "Editorial Views and Reviews," Christian Leader 2-3-1925, 4.

_________. "Editorial Views and Reviews," Christian Leader 12-22-1925, 4.

_________. "The Lausanne 'Conference on Faith and Order'," Christian Leader 9-27-1927, 4.

_________. "Editorial Views and Reviews - Evidently Alarmed," Christian Leader 4-27-1937, 4.

Murch, James DeForest. Adventuring for Christ in Changing Times, An Autobiography of James DeForest Murch. Louisville: Restoration Press, 1973.

Vincent, C. G. "When a Famous Motto Met its Waterloo," Christian Leader 3-21-1933, 2-3.

*A number of Christian Church leaders severed themselves from Disciples ties to stand with the churches of Christ in the period. Among those reported in the Christian Leader were O.D. Maple, J. G. Lewallen, D. H. Hadwin, Clayton W. Goe, W. G. Lagle, E. C. Koltenbaugh, Robert Sharp, Damon D. Watkins, and D. S. Ligon. Ligon had gone "digressive" in 1925 then returned to the fellowship of churches of Christ in 1928.